It’s a mid-November morning in Coney Island, and the weather is warmer than it has been in weeks. Sunbeams slant through the fog that lingers above the bright green grass of a recently groomed football field. In about half an hour, the Abraham Lincoln Railsplitters, the top-ranked high school football team in New York City, will take the field for their quarterfinal matchup against the New Utrecht Utes (ranked seventh). Lincoln is a powerhouse this year. It has steamrolled opponents (including New Utrecht, in week four) on its way to a 10-0 record. Win today, and it will host a semifinal matchup next weekend to determine one spot in the city championship, to be played December 10 at Yankee Stadium. It’s a perfect day for football.

Established in 1929, Lincoln is known for lots of things, but until recently, football hasn’t been one of them. The school’s athletic reputation resides on the basketball court — it graduated arguably the two most famous prep hoops players in New York City history, Stephon Marbury and Sebastian Telfair. It is where Jesus Shuttlesworth became the number-one basketball recruit in the country in Spike Lee’s He Got Game. Marv Albert was a Railsplitter.

Crooner Neil Diamond and drummer Buddy Rich roamed the halls of Lincoln. So did the writers Joseph Heller and Arthur Miller. Lincoln even boasts three Nobel Prize laureates in the sciences.

The football program does not totally lack for bright moments, though. Lincoln won city championships in 1993 and 2011, and has finished with a winning record in each of the last four season. Its the heavy favorite to win it all this year, but first, it’ll have to get through New Utrecht. The players, clad in navy blue jerseys and silver helmets that glint in the sun, sprint out to the hip-hop anthem “Hell & Back,” by Kid Ink.

It is a fitting battle cry. This area was hit hard by Hurricane Sandy last October; one fan tells me that the south upright wound up in the north end zone. The Railsplitters used Lafayette High School’s football field for the remainder of the season. After going 12-1 in 2010 and 13-0 on the way to the championship in 2011, the team slipped to an 8-3 finish in 2012, losing in the semifinals of the playoffs.

This season, the Railsplitters are trying to rebuild a championship team, as the community around them rebuilds. Last week, in its first home playoff game in two years — with the goalposts back in place — Lincoln dismantled Midwood High, 56-30. As the teams line up for the quarterfinal kickoff, there’s a crescendoing buzz among the crowd. Could this be Lincoln’s year again?

“This is better than the pros, since it’s about the team first,” Reverend Bob Fezza tells me, echoing the refrain of many who prefer amateur sports to professional. “They’re being schooled on what it’s like to play together, put aside differences, make something out of your life. It prepares them to be better people, regardless of where they come from.”

Fezza’s son coaches the offense for Lincoln, assisting head coach Shawn O’Connor. As we talk, that offense marches down the field, scoring on a long run by fleet-footed senior running back Leroy Hancle. 7-0 Railsplitters.

“That’s why we’re gonna win the championship!” exclaims a woman nearby. “For Coney Island!”

The woman is Donna Moore, the mother of quarterback Javon “Spanky” Moore, but she insists on being called “Spanky’s mom.”

“That’s how people know me,” she says. “And that’s Spanky’s sister and there’s Spanky’s grandma. We’re all family.”

Moore says that the team means a lot to the community, especially after the hardship of the last year. It’s a claim I hear from a lot of fans here, an echo of the media narrative that surrounded every New Orleans Saints home game after Hurricane Katrina. There is an escapist element to sports. With their concrete rules and clear outcomes, sporting events condense the complexity and the often-irrational breaks of life into a simple reckoning. You still either win or lose, but sports give you the illusion of justice and the promise of another chance tomorrow. We identify with our favorite teams because they are a vessel for camaraderie, allowing us to vicariously experience victory or defeat as a tribe. And we identify with our favorite players because at the highest level, they are the greatest actors of the human body. Underneath the symbology of war, sports are an expression of human physical potential. When your son is one of the fastest players on the field, you not only feel more hopeful about his life — you feel better about yours.

“I wish this year could’ve happened last year,” Moore says. “My son wanted to bring the championship home more than anything.” Just after she says this, hand to God, Spanky throws a screen pass to receiver Carlos Stewart, who breaks a tackle and scampers into the end zone. 14-0, Lincoln. On its next possession, New Utrecht obligingly goes three-and-out. Lincoln marches right down the field and scores again — this time it’s Antoine Holloman Jr., the team’s leading rusher, celebrating in the end zone.

On the bleacher above us stand Spanky’s youth team coach, Bryan Holloway, who coached a few of the Railsplitters since they were ten years old, and Spanky’s grandma, Carol Lyons. She’s “out here with knee replacement,” filming the game, as always, with her camcorder.

Lyons considers herself the team’s “adopted grandma,” and she may just be its most ardent fan. Earlier in the week, she called up the Bay News Brooklyn paper after its coverage slanted too heavily, in her opinion, toward New Utrecht. “I was pissed,” she says. Although she is known in this crowd for her ubiquitous presence at Railsplitters activities, she divulges that she has, in fact, missed one game, although further conversation reveals that she actually just missed a scrimmage. Mere days after her knee replacement, she was back in the stands — first with a walker, later with a cane. She has neither with her today.

“They want me to walk with the cane up here, but I have so much stuff to carry,” she says. “I supply drinks, too.”

Down on the field, the Railsplitters keep putting up points: a deep seam route for a long touchdown, a blocked punt recovered in the end zone. Early in the third quarter, the score is 39-0. Lincoln’s defense, led by senior tackle Thomas Holley, stifles New Utrecht. Holley is 6’4” and weighs 305 pounds, an immovable boulder of a lineman. Although he has only played two years of high school football, Holley is the number one prospect in New York state, and the seventh-ranked prospect at his position in the country. According to a report from ESPN, he has offers from the likes of Penn State, Alabama, and Ohio State.

Stan Rosenbaum and Stan Allman stand together off toward one end of the sideline. Their sons played football at Lincoln and graduated in 1991 and 1992, respectively. Rosenbaum’s son now works for JPMorgan Chase; Allman’s is a correctional officer.

Together, Rosenbaum and Allman run the Railsplitters football parents association, which schedules and supplies the concession stand (“the best in the city”), organizes fundraisers, and provides other support, as needed, for the coaches and players. Rosenbaum sports a thick grey mustache; Allman a salt-and-pepper goatee and a newsboy cap. They have been coming to games together “since 1875,” Rosenbaum says, dryly. “We’re a package deal.”

The two men complete each other’s sentences, laugh at each other’s jokes, and lament that the stands are less than filled. They are like a slightly more agreeable Statler and Waldorf. I ask what they like about high school football:

“It teaches the average guy how to be a man,” Rosenbaum says.

“You see the difference from when they came in as boys and leave as men,” says Allman.

“Strength. Coming to school with a purpose.”

“Leadership. Working well with others.”

“Since Coach O’Connor came on, there’s a 98 percent graduation rate.”

“That’s a fact.”

“He does a wonderful job with these kids. He’s a leader.”

The game on the field has ended, and both Stans disperse to mingle with other parents and the players as they leave the postgame handshake line. The Railsplitters have won 39-8, and now await the winner of today’s other game, between Flushing and New Dorp, in Queens. The team takes a knee near the 20-yard line, on the field that at this time last year was ripped up.

“We’re getting there,” Coach O’Connor tells them. “Seniors, you’re going out the right way. Next week is your last Lincoln home game. Let’s get back to work tomorrow.”

The team breaks from its huddle and scatters in all directions, toward parents, girlfriends, the train. Holley is being interviewed on camera about his next college visit, and a couple of reporters surround Coach O’Connor. After deconstructing key plays in today’s game and refusing to speculate about next week’s opponent, he responds to a question about the importance of home field advantage.

“That was one of our goals during the season,” he says. “It feels great to be home for the playoffs. We didn’t play our home games last year. We lost a lot of equipment, we got displaced. But none of them” — the team — “came in here and complained. They just got right to work. They understood that the community was a bigger thing, above them, and that maybe playing, and winning, and helping the community around us — that would be a positive thing for everybody.”

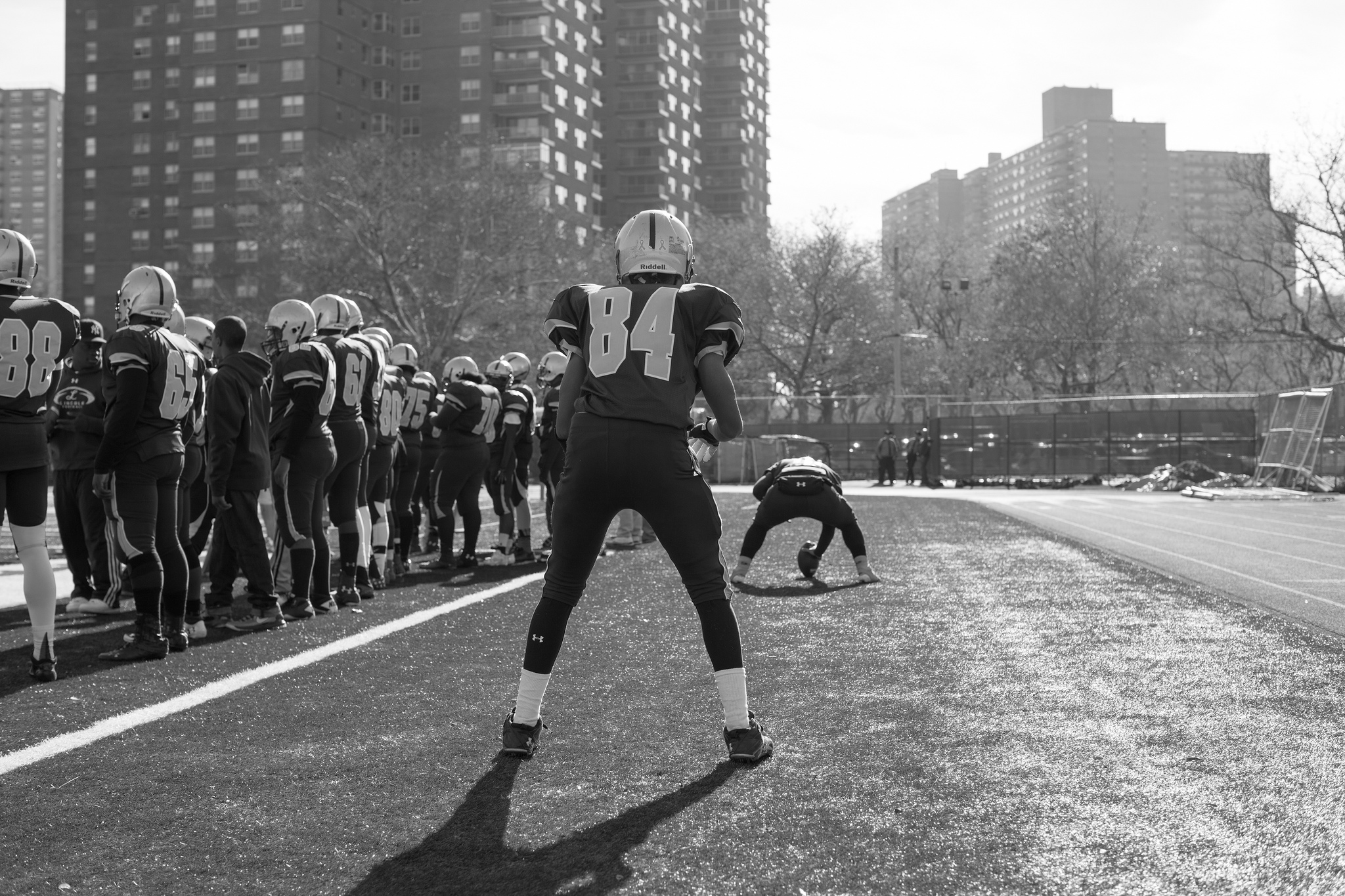

Senior Railsplitter strong safety Jahsi Meade pumps up his teammates moments before the game against New Utrecht.

Junior quarterback Paul Litvak practices snapping the ball to junior wide receiver Devon Brown.

A line judge watches the action in the first quarter.

Lincoln fans cheer on the home team.

Coaches from New Utrecht (left) and Lincoln watch the game from the roof of the school.

The Railsplitters’ cheerleaders pump up the crowd.

Senior lineman Douglass Powell and his teammates wait on the field at the end of the first half.

Coach O'Connor leads his team off of the field at halftime.

Carol Lyons, Spanky’s grandmother and the self-appointed “adopted grandma” of the team, films the action on the field.

Junior running back Luis Rodriquez and junior cornerback Maurice Allen celebrate after Lincoln’s 39-8 win over New Utrecht.

Children play on the field after the game.