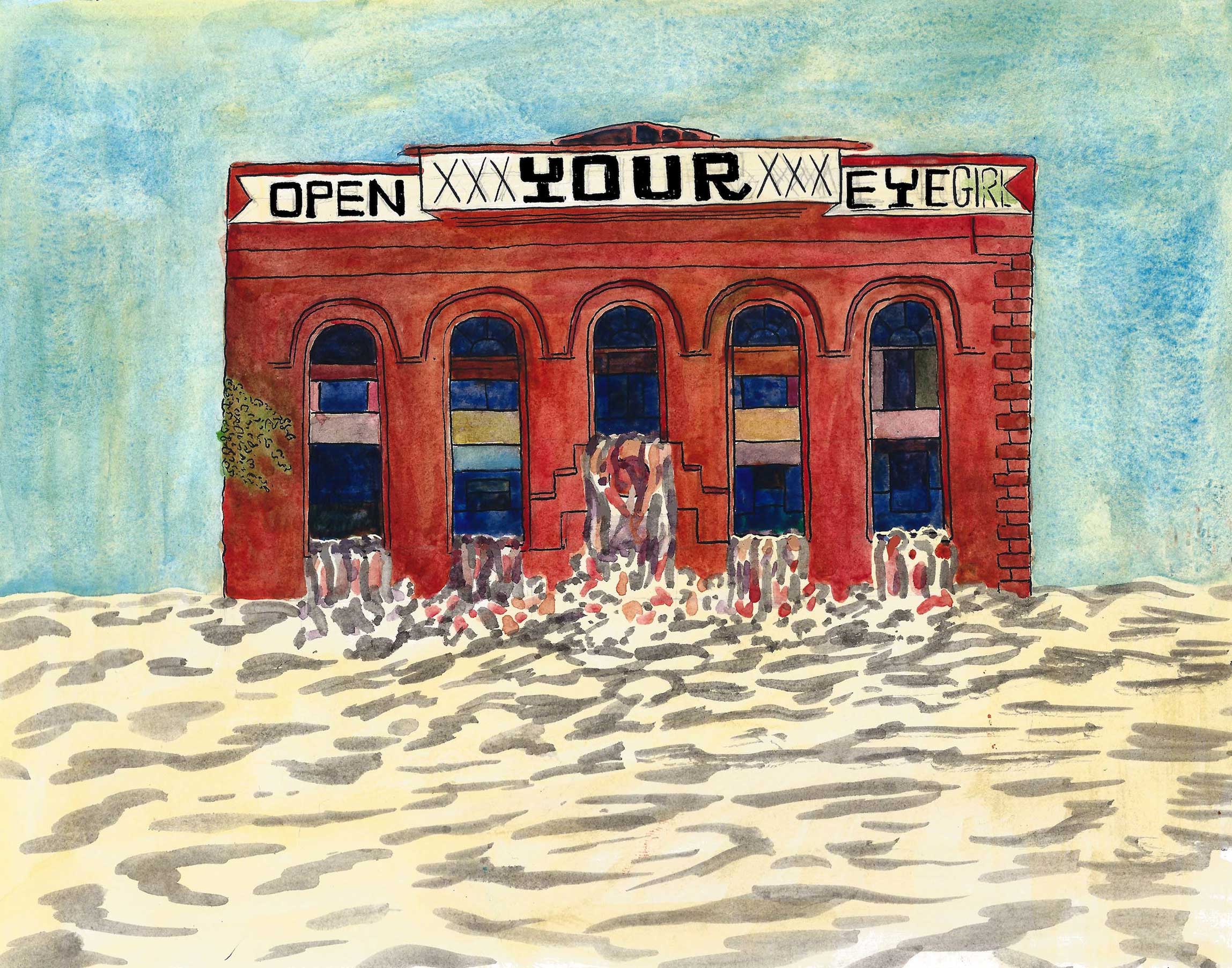

Six months ago this week, Coney Island — a place once famous for its millions of lights — went dark. Homes were flooded with four or more feet of water and front yards littered with debris. At the Coney Island Houses, people were trapped in their apartments and so much sand was pushed inland that the ground below began to resemble the beach itself. In nearby Sea Gate, people’s living rooms were washed into the ocean; a 90-year-old woman and an 87-year-old man drowned in their homes.

Images of Coney’s devastation were everywhere after Hurricane Sandy, and then the area went quiet for a few months. Emotionally and economically, Coney Island feeds on sunshine, and there was little to be had this winter. Locals spent the winter months repairing their homes and businesses, hoping that by spring a sense of normalcy might return to the neighborhood.

On a Friday afternoon in March, the area was mostly silent. One sound stood out: a storefront gate being pushed up, then another. The businesses that had lain dormant all winter were beginning to open. Disaster relief helped and the coming season for the amusements promised to bring a much-needed influx of visitors and money.

But normalcy remains far away for Coney Island, one of the most flood-prone areas in the city. Global climate change, which brings with it rising sea levels and — many believe — more frequent major storms, threatens to change the face of this area forever.

A few days earlier, on a chilly Thursday night, 200 people squeezed around circular tables at P.S. 58 in Carroll Gardens. In puffy jackets still wet with snow, they chattered excitedly and stuck neon stickers on giant maps of Brooklyn. These weren’t students working on an art project, but Gowanus and Red Hook residents brainstorming ways to protect their neighborhoods from ecological disaster.

As they settled in to work, a man with thick black glasses and a boyish face addressed the room. “Although we’re trying to prepare the entire city for climate change, certainly we as a city and as a country owe a special duty to these most impacted areas,” he said.

The man was Marc Ricks, a former Bloomberg administration official lured back from Goldman Sachs for a few months to work on recovery efforts. He had come to gather feedback for the Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency, the city’s multi-pronged response to Sandy. After Ricks explained the basic goals of the project, volunteers spread throughout the hall began asking residents questions. What had the city done well in the aftermath of Sandy? How could the city have done better? How should the city prepare better next time?

These questions are part of the city’s Sandy recovery effort, but they are also part of a larger plan for its future. Neighborhoods like Red Hook and Gowanus or Coney Island are still rebuilding. But even as locals seek to fix what Sandy damaged or destroyed, they’re facing an unpleasant reality: this could happen again.

And it could be even worse. With climate scientists now predicting a three- to five-foot increase in sea levels over the next century — a rise significantly outpacing predictions from the mid-aughts — a future storm like Sandy could push the water that devastated so much of the city even farther inland. If current predictions are accurate, rising global temperatures will bring more frequent, stronger storms, meaning low-lying areas and much of the Brooklyn waterfront could face repetitive, potentially catastrophic flooding.

In the past decade, the Bloomberg administration has put significant resources into assessing the potential effects of climate change on the city. That has only intensified after Sandy, which killed 48 people in New York City and caused more than $19 billion in damage. The city’s most vulnerable areas have been identified, major infrastructure projects have been proposed, and smaller steps have been taken to make parts of the shoreline more storm-resistant.

In neighborhoods like Red Hook or Coney Island, where residents affected by Sandy are still picking up the pieces, the demands for city action on climate change are coming loud and clear. Even beyond affected neighborhoods, Sandy spurred a spike in public awareness of climate change issues. With billions in federal aid dollars pouring into city and state coffers for Sandy recovery, and with the devastation of the storm still fresh in the public’s memory, the city has an unprecedented chance to prepare for an uncertain future.

But the city faces major challenges in translating research and talk into action, ranging from powerful developers who want to continue the lucrative build-up of the Brooklyn waterfront to uncertainty about the efficacy of massive infrastructure projects (some estimated to cost tens of billions of dollars) to control waterways. Any major initiative would likely necessitate cooperation between the city and New York state, other coastal states in the region, and the federal government, which adds yet another layer of complexity to the equation.

Academics are calling Sandy “the storm that launched a thousand conferences.” The city has assembled a decade’s worth of research on its vulnerability to climate change. It has notepads full of community feedback from those who live and work in the neighborhoods most impacted by the storm.

As a team of scientists, developers, and politicians puts the finishing touches on the city’s official response plan, the question remains: Can these neighborhoods be saved?

The latest research shows that low-lying areas of Brooklyn are facing a significantly wetter forecast than residents might realize. Current climate change models, which account for potential rapid ice melts from Greenland and the polar ice caps, make the results of a storm in the 2050s look similar to what the city faced after Sandy.

Adam Sobel, a professor and applied scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, has spent the past few months capitalizing on interest in Sandy’s destructive power to talk about long-term risks for the city. Lamont-Doherty is a major center for climate change research, and many of Sobel’s colleagues have spoken forcefully about the threat the city faces. Sobel has been saying the same thing for months at events across the city: rising sea levels are going to mean more devastating flooding for low-lying areas in the coming decades.

Sobel, slight with soft brown eyes, cuts an unassuming figure, but his words capture the gravity of the situation. “It won’t take a Sandy to create a flood like that because the waters will be starting at such a higher level,” Sobel said. “These low-lying neighborhoods will start to be inundated when someone sneezes and you have so much sea-level rise.”

At a recent “Science Behind Superstorm Sandy” event at the Museum of the City of New York, Sobel shared the stage with William Solecki, a geography professor and interim director with the City University of New York’s Institute for Sustainable Cities. Solecki has seen the city’s research efforts up close as the co-chair of the city’s Panel on Climate Change, established in 2008 to establish a set of baseline projections for the effects of climate change on the city.

The panel’s 2009 report estimated that sea levels would rise 12 to 23 inches by the 2080s. By then, the panel found, a flood equivalent in magnitude to the “100-year flood” of today would occur every 15 to 35 years. (The “100-year flood” is a term of art used by scientists, engineers, and insurance adjusters to describe a flooding event that has a predicted one percent likelihood of occurring in a given year.) As climate change creates a new normal for flooding, each flood will also bring more water with it. Today’s 100-year flood produces a storm surge of 8.6 feet for much of the city, but the report warned that by the 2080s, a similar event could bring with it up to 10.5 feet of water.

Since 2009, the outlook has grown grimmer. Solecki explained that the climate change panel’s projections did not use the “rapid ice melt” model, which incorporates sea-level trends over the last 8,000 years and produces much higher projections for sea-level rise. Four years ago, a scientific consensus had not yet developed around the rapid melt model, which some worried exaggerated the effects of climate change. The panel’s projections of a one- to two-foot sea-level rise by the 2080s were based on more conservative modeling. But recent data has bolstered support for the rapid ice melt model, and scientists are now predicting sea-level increases as great as five or six feet.

Pointing at a map of New York City, with areas flooded after Sandy marked in bright purple, Solecki said that current science shows severe flooding is likely to affect those neighborhoods far more frequently than previously thought. “As that water starts to raise, that [flooding] event — not so much that it’s any more or less strong, but because there’s more water around — it could reach that inundation zone every one to two to three years by the 2080s. And this is obviously the thing that really opens eyes with respect to development along the coast.”

In Brooklyn, those estimates could mean neighborhoods like Red Hook, Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and other areas on the waterfront will be inundated every few years; with water also starting to reach farther inland, neighborhoods like Gravesend and Canarsie will also be at risk of flooding. Flooding of that magnitude would affect almost 80,000 Brooklyn residents and more than 32,250 homes.

That’s not an assessment of future risk, though, since few parts of the borough are changing or growing as rapidly as the north Brooklyn waterfront. Brooklyn is New York City’s fastest-growing borough, and some census tracts doubled and tripled in population between 2000 and 2010 — mostly those clustered around Williamsburg and Greenpoint. Other areas still saw significant jumps, like one section of Red Hook’s Columbia Street waterfront, which saw a 24 percent increase in population during that period.

The population boom in these neighborhoods has been part of a larger trend of growth in the city. But the influx of people and high-rises to some waterfront neighborhoods is also a direct result of the Bloomberg administration’s efforts to transform the city’s waterfront. Under Bloomberg, large swaths of the waterfront have been rezoned for residential development and new parks, like Brooklyn Bridge Park and East River State Park, now dot the waterfront.

Since the city rezoned the north Brooklyn waterfront in 2005, building permits issued have vastly outpaced those issued in any other borough. Much of that development has taken the form of apartment towers in Williamsburg and Greenpoint, neighborhoods that fared well during Sandy. The city has mandated that new developments along the waterfront be built above the flood zone for a 100-year flood; some developers have also sought to harden new buildings, placing boilers and electrical equipment on higher floors.

If the city were to face another Sandy-like storm in the near future, steps like these could provide a measure of protection to north Brooklyn. But in the longer term, the picture becomes murkier. The area of the borough thought to be safe from flooding will continue to change, and it could change rapidly.

As the building boom continues and the waters rise, critics say that developers, and the city, may be tempting fate.

“There’s a lot of tension there,” Sobel said. “The city is trying to be proactive and plan. There’s still so much money in waterfront real estate that it’s hard to stop the development.”

It’s clear that the city won’t be backing away from developing the waterfront, where there’s still room to build (and money to be earned) for developers. For the city, development allows neighborhoods to grow and absorb new residents and businesses. It also brings construction jobs and tax dollars — both attractive to politicians. A recent city report on the effects of Hurricane Sandy referenced the “significant investments” along the Brooklyn waterfront, then concluded, “These efforts will continue with the full confidence of the City.” Mayor Bloomberg has also said the city remains on the right course.

If the administration sees the apparent cognitive dissonance, it’s leaving the Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency to sort it out. The SIRR, the city’s effort to turn the data and institutional knowledge it has amassed into a clear path forward, launched in December 2012. Later this month, it will release a major report that will draw upon the input of climate scientists, insurance experts, city officials, and residents of affected neighborhoods.

In the past few months, the city’s Economic Development Corporation — the president of which is heading up the SIRR — has been tight-lipped on climate change. A spokesperson for the EDC said the agency doesn’t want to pre-empt the SIRR report. Community outreach meetings in recent months have left residents of the city’s most vulnerable areas alternately curious and confused. Whatever the specifics of the report, what will matter to them is whether the city is ready to take decisive action.

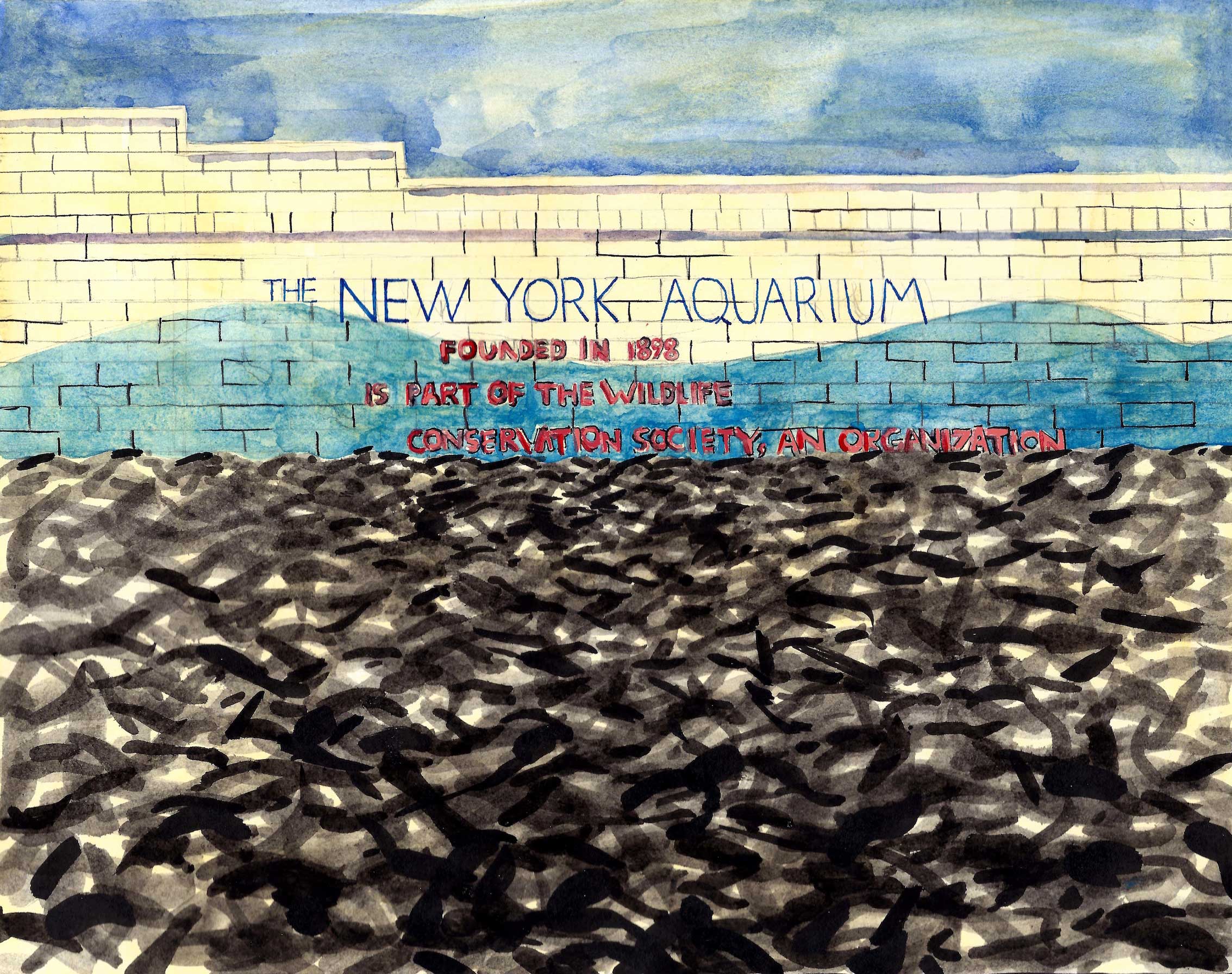

At the southernmost tip of Brooklyn, on Long Island’s far western shores, a hammerhead-shaped landmass juts out into the Atlantic. Once an actual island separated from land by the Coney Island Creek, Coney Island — or at least the middle of it — is now connected by landfill to the rest of Brooklyn. The creek survives in two sections, on Coney’s eastern and western ends, where it flows into the Atlantic.

Moving from west to east, Coney includes the neighborhoods of Sea Gate, Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and Manhattan Beach. During Sandy, the storm surge of the Atlantic washed over the boardwalk and flooded beachfront businesses. But some of the worst flooding occurred on the western half of Coney, where the creek overflowed its banks, leaving the area under four feet of water.

On one of the first warm days of spring, Coney Island resident Elena Voitsenko, who lives a block from the ocean and two long blocks from the creek, tended to a chicken coop at the Boardwalk Community Garden. Spotting a couple of khaki-colored eggs, she bent over and scooped up the day’s take, which she deposited in a plastic box marked “fishing nets.”

She stood up, slowly, and surveyed the acre or so around her. The garden, which sits just beyond the boardwalk along West 22nd Street, was once beautiful. Now, it hardly resembled a garden at all. Sandy dumped four to six feet of sand — and a lot of refuse — over the entire area. With half-buried lawn chairs and oil drums poking out from the sand, the garden, at first glance, looked like a junkyard.

Voitsenko lives in a small apartment building across the street from the garden. She was trapped there during Sandy, and she waited in fear as the waters rose around the building. Her apartment wasn’t damaged, but like the rest of the neighborhood, she lost power. She witnessed the devastation inflicted by the storm; and then there was the garden, long the pride of the block, rendered unrecognizable. “The water ruined everything,” she said. “The first day, I looked out the window and thought, ‘Why is it white?’ And it was sand.”

She is hoping the city will help fix the garden, to help the block return to how it was before Sandy. For Voitsenko, considering the possibility of frequent severe flooding is too much to bear. “I don’t even want to think about it,” she said, laughing ruefully and pulling her large, worn coat closer. “I’m heartbroken.”

Even if the garden is repaired, it faces an uncertain future. The city’s Comprehensive Coney Island Rezoning Plan, approved by the City Planning Commission in 2009, proposed converting Voitsenko’s garden into an official park, located on the edge of a new development zone. Under the plan, the city rezoned wide swaths of the area and purchased more than seven acres of land around the amusements to help spur development.

The Bloomberg administration has been trumpeting the plan as a new chapter for Coney Island, and it’s already invested considerable time and resources in advancing it. Luna Park and the Scream Zone, the area’s first new amusement parks in more than 50 years, received $6.6M in subsidies and the city has estimated it will spend $150 million on infrastructure improvements for the neighborhood over the next three decades as part of the plan.

Here, where the Elephantine Colossus — a twelve-story elephant-shaped hotel with windows dotting its sides and legs — served vacationers (and prostitutes) at the turn of the twentieth century, where the Culver and West End subway lines created a “nickel empire” in the twenties, the city hopes a new empire of recreation and real estate will rise. (“The plan will bring this beloved icon back to life,” boasted Department of City Planning Director Amanda Burden in 2009).

It’s an alluring vision, but the neighborhood of Coney Island is more than just a few new rides away from its heyday. Today, only a tiny portion of Coney Island holds any attractions at all. The vast majority of the neighborhood looks like the city’s other low-income areas: huge blocks of spare, looming red-brick New York City Housing Authority towers, by design placed far away from the heart of the city and from all major economic activity. There are few places to shop or buy groceries, and vacant lots are everywhere. Unemployment is high, something the Alliance for Coney Island, a group with close ties to the Economic Development Corporation, has tried to combat by hiring residents to help with Sandy recovery efforts.

Then there’s the question of what more development will mean for an area so vulnerable to climate change. With its location between Coney Island Creek and the Atlantic, Coney Island will need to prepare not only for big increases in storm surge from a Sandy-like storm but also for routine flooding. New housing or attractions at Coney Island — all of which is located in the city’s primary evacuation zone — mean more people and resources at risk during a storm. The hotels and apartments in the redevelopment plan will be required to sit above 100-year flood levels, but as the oceans rise, what constitutes a “safe” height will change.

Developers and city officials don’t seem to be letting up on their ambitious vision for the peninsula, which includes the expanded amusements but also high-rise apartment buildings and new hotels. The recession and Sandy stalled the plan — the high-rises and hotels still exist only on paper — but the long-term vision is still intact. Meanwhile, the Economic Development Corporation’s “Waterfront Action Agenda,” released last May, referenced Coney Island as part of the plan to “enliven” its waterfront, with no mention to how the new rides, hotels, or apartment buildings would be able to withstand the effects of climate change, another focus of the report.

City Council member Domenic Recchia shepherded the rezoning and redevelopment plans through the City Planning and City Council approvals in 2009. In the wake of Sandy, he hasn’t backed away from his support for the redevelopment, but he’s also pivoted to focus on neighborhood’s immediate future.

Recchia, who lives in Gravesend and represents that neighborhood as well as Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and Bensonhurst, has said that “long-term” means little to his constituents, who are still trying to put their homes and businesses back together.

“Twenty-five percent of the businesses here are still not open,” Recchia said in mid-April. “McDonald’s is still closed, Nathan’s is still closed, the Citibank is not opened up, the Chase Manhattan Bank building needs to be knocked down on Mermaid [Avenue],” he said, continuing on with a long list of examples. “Long-term planning is good, resiliency is good, but let’s get these businesses up and running.”

“Let’s get people back to work. Let’s renovate those homes so people feel like they have their lives back. Then we can tackle these issues of what they need to do to stay there.”

Responses to climate change can be roughly divided into two strains: sustainability refers to managing the role humans have in hastening climate change; resiliency refers to managing the impact climate change will have on humans. In a recent New York Times op-ed, researcher Andrew Zolli defined resiliency as “how to help vulnerable people, organizations and systems persist, perhaps even thrive, amid unforeseeable disruptions,” in contrast to sustainability, which “aims to put the world back into balance.” New York City can’t do anything about global climate change, so city officials are focusing their current efforts on resiliency.

For New York, resiliency could include preventative measures like waterproofing the first floor of a Coney Island community center or requiring supermarkets to put generators on roofs instead of in basements. It could also include major infrastructure projects, like expanding wetlands in coastal areas to absorb storm surges or constructing sea gates to control the flows of the Atlantic Ocean and the Hudson River.

Wetlands are a broadly popular option. Sea gates, which have been deployed effectively in other countries, have been more polarizing. Sea gates can only redirect water — they can’t stop it altogether. All the redirected water would need to go somewhere, and that could mean massive flooding in areas not protected by the gates. Sea gates would also be enormously expensive, with cost estimates for a barrier system in New York Harbor ranging from $6 billion to more than $20 billion.

Mayor Bloomberg likens sea gates to the gargantuan highways constructed by Robert Moses, which didn’t solve the problem (traffic) they were ostensibly created to solve and which left some neighborhoods untouched and flattened others. There is also the very real possibility that the city pours billions of dollars into sea gates only to discover that the barriers are no match for nature.

Whatever approach the city ultimately takes to resiliency, it’s likely to cost a fortune — and be the source of significant controversy. Already, people are lining up for battle. When the city released a preliminary plan for spending $1.77 billion in first-round federal disaster relief, Recchia knocked a proposed earmark of $327 million for resiliency efforts. Calling the 32 percent resiliency set-aside “misguided,” he urged the city to wait for community feedback and “to place more emphasis on immediate recovery and rehabilitation needs.”

Recchia said he is thinking about the broader issues — he called for a sea wall to be built along the northwest corner of the peninsula and for the construction of sand dunes along the boardwalk — but he also emphasized his constituents want solutions to their immediate recovery needs. These are undoubtedly immense, especially for local businesses seeking to open their doors in time for the lucrative summer season. “When I meet people, and I bring up what should be done for ten years down the line, they say ‘What about now?’” Recchia said.

The political pressure to deliver for constituents now is real, and there’s little reward for being forward-thinking. There are serious short-term issues to address and the neighborhood is anxious to attract developers and jobs. But if local politicians can’t — or won’t — force the neighborhood and the city to plan for Coney’s future, who will?

Eddie Bautista, the executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, a nonprofit that brings organizations from low-income communities together to advocate for healthier neighborhoods, said he trusted Recchia, but offered a warning: “What’s the definition of lunacy — doing the same thing over and over and expecting something new to happen?” he said. “If you do the same thing, you’re just asking for that investment to get wiped out again in the future.”

In the short to medium term, Coney Island will need to make serious preparations for frequent flooding.

But even if it’s able to stave off inundation for years or decades, the neighborhood faces a larger question: How far can resiliency take it?

Cliff McMillan, a principal with the engineering firm Arup, offered a sobering analysis. “It’s pretty difficult to talk about resiliency efforts if you know you’ve got a situation when you know that a quite-likely storm will inundate you completely,” he said. “There are no easy answers for that.”

At Red Hook Houses West, where thousands of residents were without heat, hot water, or power for weeks after Sandy, resident Orlando Betancourt sat on a metal bench in front of his building every day after dropping his son off at elementary school. It had become a ritual: staring at the temporary boilers still running a few yards off, the scaffolding along the front entranceway, the line on the bricks that marked the height of the floodwaters.

“Are we even supposed to be here?” he asked. “That’s still my question. Are we supposed to be in these buildings?” Short-term, long-term, he said his concerns about living in the buildings were the same. “If it’s dangerous for people here, they need to start placing people in other buildings.”

If Coney Island’s vulnerabilities make it a worst-case scenario for sea-level rise, Red Hook is more representative of the challenges facing low-lying neighborhoods across the city. There is more variation in Red Hook, where some blocks along the waterfront are extremely vulnerable, and others, on higher ground, are farther from harm’s way.

What Red Hook does have in common with Coney Island is its high concentration of poverty and public housing. Between the two neighborhoods, 74 NYCHA buildings were debilitated by Sandy, most lacking heat and hot water for weeks after the storm. Many buildings need significant immediate improvements to be capable of protecting their residents from the effects of future storms.

“One of the big lessons we learned from Sandy is that NYCHA is doing a very poor job about preparing for these types of disasters, and repairing services, and communicating with residents,” said Albert Huang, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council in New York. “Is the city considering these vulnerable communities when they are putting in how these dollars will be spent? The city needs to pay more attention to assuring that the most vulnerable communities — communities of color, low-income communities, areas where there are public housing — these are the neediest and often the most overlooked.”

Public housing is getting some immediate attention, as the Bloomberg administration prepares to spend the $1.77 billion infusion of federal disaster relief. The city’s initial plan allocates $120 million to install emergency generators in 100 vulnerable public housing buildings. But it also says that the Housing Authority is still “considering” basic measures like raising boilers above ground level because funding sources for those improvements are still unclear.

The plan, which lays out how the city will spend the $1.77 billion, offers an insight into which New Yorkers face the dangers of sea level rise most acutely. More than sixteen percent of the population in areas that flooded during Sandy is over 65 (compared to eleven percent for the borough as a whole). According to a study from the State University of New York Downstate, the Coney Island-Sheepshead Bay area has the highest percentage of elderly residents of any neighborhood in New York state. People with disabilities are also overrepresented in the inundation area, where they constitute thirteen percent of the population, compared to ten percent borough-wide.

The demographics of Brooklyn’s most vulnerable neighborhoods — and the age of most public housing — make the risks of inaction even more severe. The disabled and the elderly are least equipped to deal with the power outages or shortages brought on by flooding.

“Especially in Brooklyn, these are the same communities where they, not only are they vulnerable to floods, they’re also vulnerable to health impacts and other effects of climate change,” Huang said.

With the release of the SIRR only weeks away, people like Huang are hoping the city’s comparatively strong recent record on climate change will translate into action.

“This administration obviously has a time clock attached, and I think what the mayor is really hoping to do is create something that will succeed his administration,” said Craig Hammerman, who serves on the Special Initiative and is the district manager of Brooklyn’s Community Board 6, which includes Red Hook and Gowanus. Mayoral candidates have so far followed Bloomberg’s lead, endorsing or supporting waterfront development efforts.

Residents of places like Red Hook are also looking for action. Bautista, the head of the Environmental Justice Alliance, said he recently had meetings with SIRR officials and with U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Shaun Donovan to present its list of recommendations, some of which overlap with the city’s plans, like emergency generators for NYCHA buildings. “There’s been some openness when we talk to them, but beyond that I’m reserving judgment,” Bautista said. “It’s incumbent on us not to assume that government is going to get it all right. We have to call attention to our vulnerabilities.”

The uncomfortable reality is that there aren’t many simple solutions — that’s part of the reason the city has struggled to make concrete progress to date. “If you define success as, ‘Are things being built?’ I think you’d have to say, ‘not so much,’” Sobel said of the city’s efforts so far. McMillan agreed, saying he wouldn’t characterize the city as having acted in significant ways yet.

“There is a lot of talk going on, and of course there are emergency measures,” he said. “But beyond emergency steps that have to be taken, I don’t think we’re really doing much about it, we’re just talking about it.”