In August, on the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, the street photographer Ruddy Roye drove a red Chevy Malibu around Bedford-Stuyvesant, looking for someone dressed in an American flag. He wanted to add new subjects to his Instagram photo series, which are organized by hashtags, among them #flagseries, #blackportraiture, and one of the largest collections, #bedstuyportrait. He had no luck until he stopped at a red light on Malcolm X Boulevard. Then he saw it: the right subject, framed perfectly. A black man, wearing an American flag t-shirt, walking under the Malcolm X street sign.

Roye was ready to jump out of the car and ask the man some questions. Where did he get the t-shirt? What did the American flag mean to him? As with his other subjects, Roye planned to talk to the man for about ten minutes to get details for his captions, which sometimes run a paragraph long. More importantly, the interview would let the man know Roye was on the level with him. Only then would Roye ask if he could take his portrait. It would go out to Roye’s 26,800 Instagram followers, undoubtedly receive a few hundred likes, and, if all went according to plan, spark a discussion about race and opportunity in the comments.

But the light changed quickly, and Roye was running late for our meeting in neighboring Clinton Hill. He left the man behind. As he sat down at a table in one of the cafés that have recently popped up in Clinton Hill, he lamented the loss.

Roye makes his living taking documentary photographs for media outlets like the Associated Press. For a brief period, he took photos of Sandy’s aftermath for The New Yorker’s Instagram feed. His passion project, though, is not tied to traditional news outlets, but to Instagram itself (a tool often associated with pictures of overpriced food). Roye uses the app to publish portraits of Bed-Stuy residents, mostly black and working-class, who have lived in the neighborhood for several decades. He posts photos that he hopes will serve as both a megaphone and a translator for the voices of Bed-Stuy’s pre-gentrified community, allowing thousands of followers around the world to feel that they are implicated in the neighborhood’s problems and growing pains. Roye wants his photographs to have a social impact.

“Art is something that should do something,” he says. “It should move something; it should elevate something, illuminate something. It should stop people. Art is functional to me. It’s not ‘Oh, do you see the way the light hits that.’ No, fuck that. That’s not art, that’s ego.”

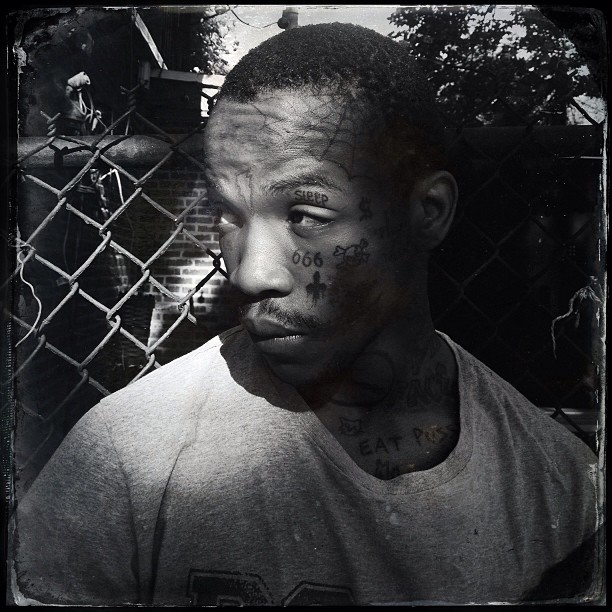

The captions he writes prominently feature his views on race and inequality, and his social mission — to change perceptions of poor, black people — guides the way he takes pictures of his subjects. He often frames them in the most flattering way possible: in one of his photos, a man with visible tattoos of a skull and crossbones, the number 666, and the words “Eat Pussy” looks mellow and even almost wholesome.

His other tactic is to find a neighborhood signifier that appears ironic next to a certain subject. He recently posted a shot of an elderly black couple dressed in church clothes under an awning for the Slave Theater, which is branded with the words “Slave #1” and a map of Africa. Roye’s messages are obvious, even to someone completely unfamiliar with Bed-Stuy.

“I’m not leaving any picture uncaptioned, for you to come up with your own idea of who that dude or woman is,” Roye says. “I want to tell you exactly who they are and their story.” For this reason, his captions are sometimes several hundred words long. His work is part documentary, part propaganda for the neighborhood’s old guard. All of the pictures on his feed are serious, but they’re easy to digest visually, making them ideal for a large following on Instagram. His best photographs are eye-catching and humane; his worst, a bit hastily shot and heavy-handed. Roye’s work belongs to a long tradition of New York street photography, but few of his predecessors had a captive, global audience of thousands — nevermind complete editorial and ethical freedom. What he does each day, driving around Bed-Stuy, is an experiment.

As Roye settled into the café’s petite furniture, stretching out his long legs and arms, I noticed that the top half of his left arm was covered in black tattoos of faces: his two young sons; his mother; and a woman, a prostitute who he says saved his life when he went to Jamaica to bury his father in 2007. The bottom half was covered in cameras. There were a few mechanical cameras — a Leica model and a 4x5 — but the place of honor, on his wrist, was awarded to an iPhone. Roye, who is 43, says he never photographed anything until he was in his late 20s, living in Jamaica in the late 1990s and considering a career change.

Growing up in Montego Bay, Radcliffe Roye’s mother, a schoolteacher, encouraged him to read all the books he could find. When he was required to write down a desired profession for a community college entrance exam, he listed journalist first, lawyer second. He dropped out of community college at 16 to apprentice at The Western Mirror, a small newspaper in the area, and worked his way up to Jamaica’s major newspapers, like the Jamaica Gleaner and the Jamaica Observer. He wrote crime and human-interest stories. “Really, any story in Jamaica is a social justice story,” he says.

But newspaper politics and the heavy editing of his stories caused him to become quickly disillusioned with journalistic writing in Jamaica. He left for the United States at 20, wandering from Kansas to California to Baltimore, where he enrolled at Goucher College. At Goucher, the Brazilian philosopher Gisele Amaral Dos Santos introduced him to existential philosophy. He started practicing Rastafarianism, which he describes as “a vehicle for living righteously,” and grew his locks. Before he moved back to Jamaica, Dos Santos gave him his first camera and told him to consider telling his stories with it. But he didn’t use it until he got back to the island. “I was very depressed when I went back,” he says. “Then photography found me.”

Roye went back to work for the Jamaican papers, this time as a photographer. His first assignment was to document the shacks that had popped up on an abandoned train line that ran from Montego Bay to Kingston. Carrying a Nikon N90 loaded with Sensia slide film, he walked along the tracks for hours a day, taking pictures of the community life there. He calculates that he walked 121 miles, and those miles are what it took for him to learn “the craft of photography.” But the art of photography was still out of reach in Jamaica, he felt. An editor at the AP told him that if Jamaican photographers could take pictures of social issues with the same dedication as the way they photographed cricket, they’d be the best photographers in the world. That made sense to him: he would go to New York or Los Angeles to develop his artistry as a photographer, and eventually return to Jamaica. He moved to Brooklyn in 2001.

His first social justice story in New York came to him under an unassuming guise, when the city’s parks department commissioned him to photograph parks in all five boroughs. In the parks located in low-income neighborhoods, he photographed broken swings, kids who might break their legs on the worn-out rubber of old jungle gyms, and trees (or lack thereof). “I learned that we have a lot of parks, and that they don’t all look like Central Park,” he says.

Roye’s photos of the underfunded parks were matched with photographs of Central Park, in an effort to get more city funding for small parks during Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s first term in office. But the public never saw the photos, and Roye still thinks about that experience when considering the impact of his Instagram work. “I take pictures to share my photos,” he explained to the street photographer Orville Robertson, when he ran into him recently. “I shot 500 parks, and no one besides the parks department ever saw them.”

Around 2003, the Magnum photographer Christopher Anderson told Roye not to try to do “the journalism thing” and instead to look at the work of Richard Avedon, the American portraitist photographer, for inspiration. Roye did, and it was a turning point in his career. “I learned that one photograph encapsulates a whole story if you do it well,” he says.

While driving his two sons, who are five and eight, to school, Roye began thinking of the project that eventually turned into #bedstuyportraits. He started by taking pictures of the people he encountered on the route from his home in Bed-Stuy to his older son’s school in Clinton Hill. “A photographer can be one of two things: a hunter or a scavenger,” he says. “A good photographer is both: he both hunts and he waits.”

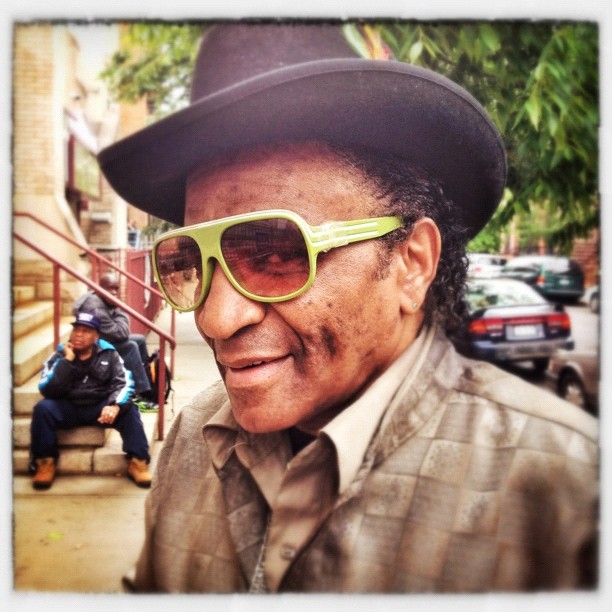

Roye took his first picture for #bedstuyportraits near Fulton Street and Malcolm X Boulevard in May of 2012. A middle-aged black man, nicknamed Sugar Bear, stood dressed in a black felt hat, a beige checkered suit, and lime green–rimmed shades. His face is in quarter-profile, with one pockmarked cheek confronting the camera. The image is kind of a play on words: Sugar Bear seems to be a cheeky character. In the background, we see a few men sitting on steps, slouched over, waiting for something. We learn from another tag, #freefoodprogram, that it’s probably for food. Sugar Bear looks at the camera out of the corner of his eye, his glance and half-smile betraying playful disbelief that someone would want to photograph him.

Roye converted Sugar Bear’s name into the tag #sugarbear. When you search for #sugarbear on Instagram, countless pictures of pets appear. Among snapshots of Chihuahuas, ferrets, and hedgehogs cuddling with their owners, Roye’s picture of Sugar Bear sticks out like a sore thumb. “Instagram hacking” is the phrase that comes to mind: Roye’s photos and tags are little mines among all the site’s inward-facing documentation.

“As I get older, I become more serious about purpose,” he tells me in the café. “Each image has purpose. I have nothing to say about people who photograph their cats, dogs, or food. But when I go through my feed and I see African-Americans putting up a picture of twerking on a day like today, it bothers me.”

Though Roye says that he doesn’t seek out particular individuals for his portraits, it’s clear from his feed that he prefers to photograph people whose faces, dress, or surroundings allow for comment on Bed-Stuy’s race and class issues. He is an avid documenter of the neighborhood’s can collectors, and he photographs many of them daily, even though he’ll usually only put up one picture per subject on his Instagram feed. Because he’s working on Instagram, he can set his own ethical standards and rules.

He has a close relationship with one of the can collectors he photographs regularly. “I’ll buy him coffee,” Roye says. “We’ll sit down and talk, and he’ll tell me his daughter is in a wheelchair and needs diapers.”

Roye describes a typical encounter: he asks the man how much the diapers cost. The man says ten bucks; that’s why he’s out collecting cans. Roye then asks: “How much money do you have in your pocket?” The man says five bucks.

“‘Here’s five dollars,’ I say. ‘Go buy it.’”

Roye is uncomfortable with playing the role of distanced bystander, a relationship often prescribed to photographers by journalistic outlets. “We’re talking about human beings here,” he says. “I’m not just the dude in the community who takes pictures. I’m part of the community.”

Roye’s community has been predominantly black since the Great Migration. But in recent years the demographics of the neighborhood have shifted, a topic which Roye speaks about in vague terms.

“I think it highlights problems with the way our society deals with certain groups,” he says, giving an example of a school frequented by affluent white children in Fort Greene, whose buildings and surrounding streets are in much better condition than a public school with predominantly black children in Bed-Stuy.

The addition of wealthier residents to the community is not inherently bad, he is careful to state. What Roye wants to change are what he feels to be racist attitudes towards the neighborhood’s existing residents. “White people, I don’t think, understand who we are,” he says with uncharacteristic bluntness. “I hope my images shed some light on the humanity that exists in the community of black folk. Everywhere I’ve traveled, black people are seen the same way. They are discriminated against by every other ethnic group. And some of this ignorance came from images. I’m trying to put out different images.”

One morning a few months ago, Roye encountered a homeless man on his way to a shelter in Bed-Stuy. Roye says he looked tired, and high. Roye approached him anyway, and asked if he could take a picture of him. The man said yes, but as Roye tells it, he followed his response with:

“I don’t know why you want to take a picture of me. I’m not a good person. I’ve killed people. I’ve stolen. I’ve tried to kill myself four times.” Roye reached out, and, in an unusual move, touched him. “When I did, he looked at me like, ‘Dude, you must be crazy,’” Roye says. “But I saw his face melt into the face of a teenager. He told me I could take all the pictures I needed.”

In Roye’s portrait, the man, rendered in black and white, is looking into the top left of the frame. His clothes are blurred so that the eye travels to the man’s face, which has a sad, yet composed, expression. “It was the softness of his eyes,” Roye says. “He looked youthful. In the picture, he’s looking away, as if thinking of the good years, and peeling back his mistakes, and thinking of how different it could be.”

Roye’s best Instagram work invokes the philosophy and practice of another black photographer who documented a changing neighborhood: James Van Der Zee, whom Roye lists as an influence. Van Der Zee’s subject matter was mainly the middle-class residents of Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance, and he photographed them mostly in the confines of his studio rather than on the street. But his desire to bring out a sense of goodness in his subjects is part of a philosophy of empathetic, community photography that Roye demonstrates in his work.

In one of Van Der Zee’s photographs, “Attitude Counts,” a Harlem dandy leans on a cane, dressed in black striped pants and a faux fur coat, with leather gloves hanging off his other arm. A cigarette dangles between his lips. He has the same mischievous expression that you see in many of Roye’s photographs. If you look closely, you’ll see that he has a stained jacket, and the tips of his gloves have been blurred out by Van Der Zee, probably to hide stains or holes. Van Der Zee employed an unusual practice for his time, airbrushing his photographs so that any outward signs of poverty would go unnoticed.

“I start with me, and how I would like to be represented,” Roye says. “And if the clothes are dirty, that doesn’t mean I can’t photograph that person with integrity.”

Roye’s 21st-century version of Van Der Zee’s airbrushing technique is to use the various filters and tools of the Hipstamatic app, before uploading the altered image to Instagram. It allows him to blur out backgrounds and focus on the subject’s face. Sometimes, he pumps up the color of the subject’s clothes.

“Digital is psychedelic to me,” Roye says. “When I took a photograph with film, I never felt like fucking it up. With digital I feel like: punch the colors, saturate it, push it.”

Recently, three of Roye’s Instagram photos were selected for an exhibition of contemporary street photography at the Alice Austen House on Staten Island. Lined up on a wall near the window were three small, uncaptioned black and white portraits of Bed-Stuy residents. Without a backlight, they looked dark and shadowy, a bit more humble than when presented on Instagram. Roye’s Bed-Stuy photos, even the best ones, are inextricably tied to the medium: they need the long captions, the comments, and the context of the feed. His work isn’t traditional street photography, with all its rules and aesthetics, simply converted to Instagram.

“I think that if film had a platform that allowed me to shoot and have it up with the ease that Instagram does, you’d have known me ten years ago,” Roye says. He takes as many photos as he did when he walked the train tracks in Jamaica for his first assignment. But while he has thousands of rolls of film in his house that no one will ever see, his followers see his photos every day.

While trying to find an iconic March on Washington photograph, Roye took what I thought what might turn out to be one of his least convincing shots. He saw a sign for Bulleit whiskey on the wall of a bus stop at Gates and Grand. He didn’t like the ad, so he wanted to wait for a subject to sit in front of it. A few seconds later, the subjects arrived, a group of three boys on their way home from school. They sat right in front of the sign.

Roye approached them and asked to take their photo. The boys mumbled their agreement, a bit puzzled. At first, the boys’ faces were frozen in unnatural-looking smiles. Roye crouched down in the street in front of the stop, snapping picture after picture. Eventually, the boys grew impatient, and their faces relaxed, their stares harder and less goofy. The bus arrived, and Roye asked them their names and schools as they boarded. Roye seemed satisfied with the picture’s symbolic power on the anniversary of the March. “Now, I’m going to caption this with the speech that Obama is making today about what has changed and what hasn’t,” he said. “They put signs like that one only where black people live. And these boys have to see it every day on their way home from school.” He mentioned pumping up the color on the boys’ sneakers and backpacks.

The photograph went up the next day, accompanied by a 309-word caption featuring quotes from President Obama’s March on Washington speech, along with Roye’s asides. The end of the caption read, “Pictures like this one are everywhere in my hood. The gall of these advertisers to put up in our communities advertisement that speaks directly, or subliminally to a gun or drug culture that only leads to us getting incarcerated. Where is the real change. Our community has heard enough rhetoric I think.” As social criticisms go, it’s not the most precise. Yet Roye’s broader point about skewed advertising in low- and middle-income black neighborhoods reached, at the very least, the 309 people who “liked” the image.

Recently, Roye has begun to doubt the potential for his photos on Instagram to advance his professional career. It’s not about the money, Roye claims. He says he gets a lot from his Instagram work that doesn’t have monetary value. He’s more worried about developing a certain type of reputation. A friend and fellow documentary photographer who uses Instagram, Ben Lowy, warned him that editors and curators might ghettoize him as a photographer whose work would only be good for Instagram, or a photographer who only takes pictures of black people. Roye worries that it might be easier for a renowned traditional photographer to transition into Instagram than the other way around.

Roye still hasn’t gotten as many freelance assignments as he would like, despite his thousands of followers. He expected to hear from assignment editors about shooting portraits during the U.N. General Assembly meeting in September, but didn’t receive any calls.

“So maybe it’s a lack of intuitiveness on my part, that I didn’t call enough people. I get that,” he says. “But if Instagram was working for me with all those follows, somebody should have called me as a candidate.”

Roye says he’s come to a point in his career where he’s done playing around. He needs to determine what type of photographer he wants — and can afford — to be. And stick to it.

Yet Roye speaks excitedly about blowing up some of his portraits of his favorite street characters to several feet high and pasting them around Bed-Stuy in the locations where his subjects hang out, as sort of photo graffiti. They would turn the streets into a gallery. He’s also working on a crowdfunding campaign to publish a book of portraits called Common Threads, which would include many of his Bed-Stuy subjects.

Back at the bus stop, Roye rapidly edited the photograph of the boys on his phone. A man collecting cans, someone whom Roye didn’t know, picked up a stray dollar. Roye looked up from his phone and congratulated him on his find. The man was listening to Michael Jackson on his headphones and singing along to the music out loud. As the sun started to set, a woman leaning out of her doorstep started dancing along to his singing. Another man walked by. He appeared to be in his thirties, with jeans rolled at the cuffs and brown Oxford shoes. The man saw the can collector, and greeted him. They appeared to know each other well. Standing next to his blue Audi, the young man struck up a conversation about a birthday present for his wife.

Ruddy asked me what I was looking at. I asked him if he wanted to photograph the two men, one from the old guard and one from the new. He said that if he did, he would maybe photograph their reflections in a puddle, and positioned me so I could see what he was looking at. In the street water, you could make out the two men’s faces against the gray-blue sky. “But I wouldn’t photograph that,” Roye said. “Those two guys were just talking. That could mean anything. Now if they had shaken hands — that would be something.”