Two days before the Fourth of July, Judge Marilyn Go walked into the ceremonial courtroom of the Theodore Roosevelt Federal Courthouse in downtown Brooklyn. She was there to grant citizenship to the 267 people seated and waiting.

In front of her were faces of all ages and colors. The greatest numbers were from China, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Bangladesh, India, and South Korea, though there are also immigrants from Nepal, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Guyana, Israel, and Liberia; in all, over 50 countries were represented. Here was a microcosm of the global poor — a cross section of nations wracked by civil war and poverty.

Earlier in the proceedings, one woman got up to go to the bathroom, but was told to stay in the courtroom; if she happened to be out when the judge administered the ceremony, she would not be considered a citizen. One by one, the 50 or so who had anglicized their names were called to the front to confirm that they were now Kevins and Jameses. No one checked cellphones — phones and cameras are prohibited in the building — and few talked. The people here had been through at least five years of paperwork and waiting rooms to arrive at this moment. The atmosphere was some cross between a graduation ceremony and a DMV.

With a loud rap from the clerk, the 267 rose as Judge Go strode to her podium. She began a speech on the promises of America: among them, the right to vote, to freely participate in political debate and expression. Judge Go acknowledged that “our government isn’t perfect,” but encouraged citizens to feel a part of America in all the immaterial ways that make citizenship more than a certificate. She mentioned her own family’s journey from China when she was six years old, when she spotted the Golden Gate Bridge for the first time.

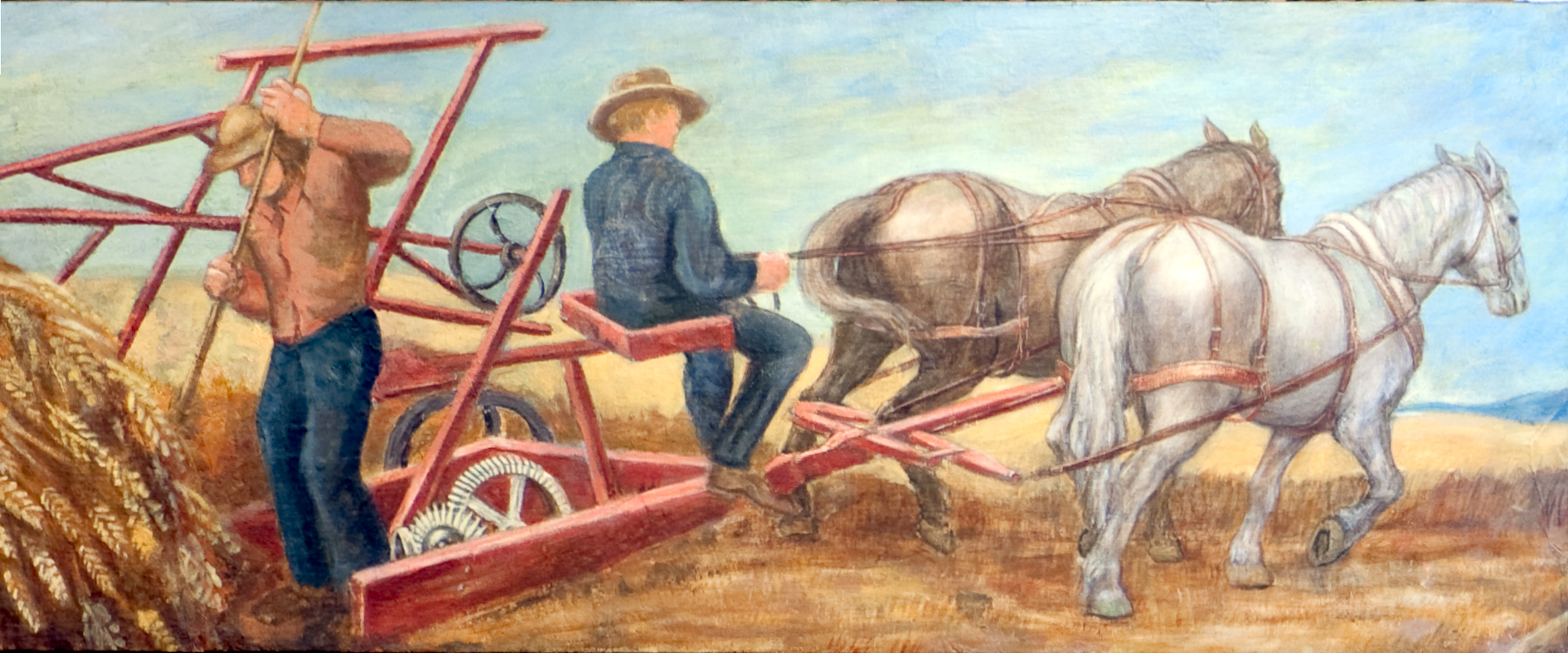

She then pointed to the wall behind the immigrants, where a row of monumental panels hung above the seated citizens-to-be. The murals depicted massive figures, some seven feet tall, large enough to dwarf the people below but small enough to feel relatable. The dozens of figures were engaged in the work of building railroads and fueling factories, debarking from ships, and beginning their lives in America.

The judge invited everyone to take in their narratives, which celebrate those immigrants’ contributions, and to place themselves within the full history of immigration to this country. Some looked up; others were too focused on the ceremony at hand. These vast images were created to welcome immigrants to the country, but a gulf of decades, in which the status of the immigrant has gone from boon to burden, separated them from the people below.

On August 25, 1937, the artist Edward Laning was dismayed to read in the New York Herald Tribune that his mural would not stay on the walls. “That Big Mural Won’t Stay Put Even If Pasted,” said the headline. New Yorkers had long been anticipating the completion of the work, due to be installed at Ellis Island, but because of a new adhesive being used, the surface of the mural was “bulging out in tiny ripples and large bubbles which had to be pricked and ripped and then pasted back more firmly.” This was not welcome news, as delays had already drawn out the project for four years.

In his memoirs, Laning, then 30 years old, would recall riding the ferry back from Ellis Island after seeing the article, leaning over the rail, and thinking, “It might be better to slip over the side and have the agony over with.” But something floating in the water stopped him: a condom. “Suddenly I was aware that the harbor was a mass of floating condoms — thousands, millions of them. I decided to wait and die some other way,” he would write.

The paste debacle was the last in a long saga of setbacks for the mural. In part because of Ellis Island’s symbolic weight and in part because of the project’s starts and stops, the press found the murals a subject of fascination. They were one project among hundreds under the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project started just a few years before. The FAP acknowledged that artists “have to eat just like other people,” as New Deal architect Harry Hopkins quipped to President Roosevelt, and set out to provide them work. (A dramatic poster advertising the project asked in bold letters, “Shall the Artist Survive?”) Under one of the largest FAP initiatives, public buildings across the nation were surveyed as potential sites for murals. The series at Ellis Island was one of over 100 in New York State alone.

Laning was not the original choice for the Ellis Island murals. Hideo Noda, a Japanese-American artist who had assisted Diego Rivera on his Rockefeller Center murals, was originally selected by FAP’s New York director, Audrey McMahon. Noda was asked to submit sketches to the commissioner of immigration, Rudolph Reimer, a self-anointed history buff whose role as commissioner allowed him final say on the art projects. Laning remembered Noda as “a gentle boy of poetic temperament” and Reimer as “a big, gruff man with a red face and white hair” who growled his words. When Noda submitted sketches that depicted a black farm hand wearing a turtleneck sweater, Reimer ridiculed him. When Reimer demanded more changes, Noda quit.

It was then that Laning received a call from McMahon. She asked him to take on a delayed project, two assistants who had been hired for Noda, and a tough boss. The situation was less than ideal for an artist. But at that time, Laning was unemployed and was borrowing money. The year before, his submission to the WPA to decorate a post office had been rejected. He also knew the call from McMahon was a command, not a request, and he took the job.

The Aliens’ Dining Room at Ellis Island was large, running over 100 feet in length, and with 800 square feet of wall space. Laning decided to use the space to show the various industries to which immigrants to America historically applied their labors. He called the cycle The Role of the Immigrant in the Industrial Development of America. The mural would depict a series of scenes from the mid-nineteenth century building of the Transcontinental Railroad to the arrival of new immigrants by boat in the early 20th century to modern factory industry. Laning sketched his ideas and brought them to Commissioner Reimer, who said, “You don’t know much about railroading, and you don’t know a damned thing about coal mining!” Reimer pointed out that the square-cut railroad ties Laning depicted were invented only 25 years before, and that the soldiers’ uniforms should have high boots. Laning made those changes, and in September of 1935, the WPA approved Laning’s design. Work commenced.

In part to avoid Reimer, Laning painted the mural in his loft studio on 17th Street in Manhattan, which he shared with his wife and rented for $40 a month. He had a carpenter erect a movable partition to hang the great panels. With the help of four studio assistants and, during the cold months, the warmth of his potbellied stove, Laning completed the cycle and invited Reimer for a visit. Away from his home territory, Reimer was “graciousness itself,” and had the murals transported to Ellis Island.

The plastic paste which caused the bubbling incident was replaced with traditional plaster, and the damaged parts were repaired. In February 1938, the murals were unveiled with Holger Cahill, the national director of the Federal Art Project, in attendance. Laning had spent the better part of eighteen months working on the murals. Their success led to Laning’s selection as the muralist for the grand landing on the second floor of the New York Public Library — probably, by his account, “because I had demonstrated at Ellis Island a capacity for endurance.” The NYPL murals, four altar-shaped works even taller than the Ellis Island panels, depict the history of the recorded word. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia unveiled the library murals in 1940. They are Laning’s best-known work, and are still in situ today.

A photograph of a young Edward Laning accompanied the New York Herald Tribune article about his murals bubbling and rippling off the walls. Dressed in a suit and tie, hair parted and with a neat mustache, Laning could pass for any white-collar worker. His look embodied professionalism in an era when artists, with their guilds and associations, comported themselves with a seriousness of purpose.

Laning was born in Petersburg, Illinois, and attended the Art Institute of Chicago and University of Chicago. He continued on at the Arts Students League of New York, where he studied with luminaries of the day like Thomas Hart Benton, one of Jackson Pollock’s mentors, and Kenneth Hayes Miller, one of the school’s most influential instructors, whose pupils included George Bellows and Edward Hopper. Laning would later write that “Miller was the Academy of his time, and not to have submitted oneself to Miller’s examination was not to have gone through the mill.”

In New York, he associated with the Fourteenth Street school, a loose group of artists with studios around Union Square that set out to portray the rapidly changing downtown New York. Miller, the elder of the group, taught most of the others, which included painters like Isabel Bishop and Reginald Marsh (whom Laning called “the greatest artist of his time”). While their contemporaries in the Regionalist movement were codifying a national art through America’s farms, towns, and landscapes, the Fourteenth Street school artists were looking to the bustling urbanism around them, finding, in the words of art historian Henry Geldzahler, “not the ease and self-assurance of an old aristocracy, but an America of vibrant contradictions.” They created lively and often humorous scenes out of the drinkers, workers, and society women around them. The group was a favorite of the Whitney Museum, one of the first major venues to exhibit Laning’s art.

Laning and the Fourteenth Streeters occupied a peculiar role among their peers in the 1930s. While their subjects were distinctly contemporary, their style was proudly anachronistic: under the influence of Miller, they drew inspiration from European masters like Rubens, Veronese, and Tintoretto. During a trip to Europe in 1929, Laning was taken by the work of Rubens, one of Miller’s favorites. When Laning was turned down for the post office commission in 1935, he attributed it to his own “baroque aesthetic”: the sweeping arrangements, soft edges, and energetic bodies that showed Rubens’ influence.

Baroque sympathies aside, Laning engaged with the artistic questions of the day; newspapers often mentioned his presence at openings and unveilings. When, in 1934, Diego Rivera refused to remove a portrait of Lenin from his mural Man at the Crossroads in the new Rockefeller Center and Nelson Rockefeller ordered the entire mural destroyed, Laning joined many of his peers in signing an open letter to Mayor LaGuardia protesting the proposed destruction. They saw the decision as “strik[ing] at the freedom of all artists” and refused to exhibit at Rockefeller Center. Laning’s circle was not as ideologically aligned, either in their art or actions, as the Mexican muralists. But the debacle must have shaken the young, aspiring Laning. Murals, the original public art, are subject to the whims of a whole body of constituents. And while Laning’s troubles at Ellis Island were not political, the Rivera incident offered a preview of the headaches that come with large commissions.

At the same time, another profound shift in art making was gaining a foothold in America. Led by the new Museum of Modern Art, New Yorkers were looking closely at European abstraction, or non-objective art. By the mid-1930s, even the WPA accepted it. The Williamsburg Murals were commissioned by the FAP in 1936 for one of the first public housing projects in the city. Because the development was primarily home to factory workers, the architect thought realist images of labor would not create a relaxed environment. Currently housed in the Brooklyn Museum, they were the first abstract public murals in the country. In 1939, New York would have its first “Museum of Non-Objective Painting” — which would later be known as the Guggenheim.

Caught between politics and abstraction, Laning and his circle were to their time something like the French Academy of the nineteenth century was to the Impressionists: a formally rigorous group that would be overlooked by critics and historians in favor of their more experimental contemporaries. Laning would, in the 1970s, dismiss the contemporary art displayed in museums as “a bad joke,” and he defended figurative, narrative work until the last.

Even in the 1930s, Laning knew that many opposed the Federal Art Project as frivolous “boondoggling” and felt it “was necessary to develop work projects that could be defended as “worthwhile.” And yet, in discussing the Ellis Island murals in his memoir, Laning does not discuss what their “worth” might be, what he hoped to communicate. We’re left with very little idea of why he chose the subject of the murals, and why he painted them how he did.

Of the dozens of figures in the The Role of the Immigrant in the Industrial Development of America, not a single one is smiling or cheerful. We see instead the grim concentration of the railroad workers and the daydreaming of the woman looking out her window. We see each step of the immigrant’s journey, from the sallow-faced arrivals, with long skirts and rumpled suits, to the laborers of the railroad and forge, whose shirtlessness marks them as laborers above all else.

The sweep of the mural’s 100 feet echoes the grand scope of its narrative: a Native American man at far left points us towards scenes of wheat harvesters, railroad workers, coal miners, blacksmiths, and arriving immigrants. The scene spans industry and geography. The railroad tracks of the central scene act like a ceremonial ribbon, guiding the viewer from one side to the other. Howard Wooden, writing for an exhibition of Laning’s work, notes that during this stage in his career, Laning “introduced diagonal movement, areas of open space, and well proportioned shifts in scale,” which replaced the flat frieze that characterized his earlier work and many other realist murals.

The people in the mural become their labor. The wheat gatherers recall Van Gogh’s famous series after Millet, and the metal workers recall a celebrated 1920 photograph, by Lewis Hine, of a man with a wrench. All of these share in common a fusion of man and labor, traditionally masculine depictions of physicality. Only one woman in the mural is shown working, harvesting wheat; a couple of women at the right carry babies and bundles. The workers seem at once at peace and in motion; the figures hammer, lift, and push, but their stances are solid and confident. Laning depicts multiple stages in each labor: railroad tracks are lain, hammered, adjusted; the wheat is harvested, bundled, and carted off.

By linking these scenes, Laning draws a continuity between labor past and present. The scenes would have pleased the WPA board that approved the sketches, with its promises of useful work as a balm for the Depression.

For this mural, Laning also moved away from, in Wooden’s words, “the tight drawing technique” to “long sweeping brushstrokes and soft contours for boldly modeled figures.” This is the “baroque aesthetic” that Laning saw in himself, something unusual for a muralist of the era. Up close, one can see the brushstrokes that blur the edges of the figures, but at a distance they lend the figures vibrancy.

Railroads were ever a subject of fascination to Laning. His sketches for the post office mural contest in 1935, which he was not awarded, were of the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. He shelved those sketches until the 1970s, when he was awarded the commission to paint them in the Ogden Post Office — one of the last projects he worked on. In both the Ogden murals and the Ellis Island murals, we are offered a sweeping panorama of railroad-as-landscape, the tracks bending with the horizon line towards either end of the scene. We see a mixture of Chinese and white men (the latter probably Irish), many shirtless, working side by side to lay down iron railings. The scene is a fitting heart for the Immigrant murals — a project of unfathomable complexity linking America’s two halves for the first time, one relying wholly on the labor and lives of immigrants.

The Works Progress Administration, aimed to create a public art — arguably the first time that idea was put forth in America, and the last time it was attempted on a large scale. Laning internalized and advocated for the ideals of public art for the rest of his life; he would later call the WPA period “our golden age, the only humane era in our history.” Art, Laning believed, not only conveyed useful messages, but held together the social order by offering employment and purpose.

In his later years, the artist foresaw an apocalyptic future for the United States. His painting The Fire Next Time, borrowing the title of a book by James Baldwin, is a nocturnal scene of ghostly figures gathering around a statue in Union Square. He predicted, in the 1970s, another great depression, but one in which “there will be no relief for anyone.” In a 1972 speech to the Fine Arts Federation, he drew the link between the burgeoning graffiti movement and the loss of a public art:

While I do not decry … the embellishment of our dreary subways with spray-can graffiti … these manifestations are the result of a frustrated appetite. If we cannot provide public sanitation the population will foul its own nest. If we can’t maintain a public art we’ll get a public nuisance.

The elderly artist, raised on the promises of a collective social project and looking out at a (literally) bankrupt city, struggled to make sense of the decay. He died in New York in 1981, just as the art world was set to boom. Farther than ever from a middle-class profession of groups and guilds, art-making at the time of Laning’s death mirrored the profit-driven individualism of the 1980s.

Laning lived long enough to see his conception of the immigrant that he memorialized become dated. The immigrant’s labor in America has shifted from industry to service, and cultural representations of immigrants, in contrast to the Herculean figures of the WPA murals, operate bodegas, taxicabs, laundries, and chain restaurants.

And in place of the great masses fueling booming industries, the popular idea of immigration is now defined by borders, waiting, and detention. Once the Ellis Island murals were finally unveiled, the grand civic institution would serve as an active processing station for only sixteen more years. 1938, the year of the murals’ premiere, was far after the heyday of Ellis Island immigration; the 1924 National Origins Act severely curtailed immigration, and the majority of Ellis Island arrivals afterward were war refugees or displaced peoples. During and after World War II, Ellis Island became a detention center for enemy merchant marines, and held suspected communists in 1950. Ellis Island ceased operations entirely in 1954, and was declared excess federal property.

The function of those Renaissance Revival buildings, which now house a museum, has been inherited by dismal successors. Today, New York’s unwanted immigrants are detained in unmarked, factory-like buildings in Queens, Manhattan, and New Jersey. Some of these detainees are undocumented; others have papers but are thrown into limbo because of criminal records.

Often these centers are government-funded but run by private companies. The infamous Varick Street federal detention facility has seen complaints of prisoner abuse and an investigation by the New York City Bar Association, but is hard to reform in part because it is run by an Alaska Native corporation. According to the ACLU, some 250 centers around the country held over 400,000 immigrants in 2011, a murky annex of America’s prison-industrial complex. They are not sites to be celebrated with federally funded art, but blind spots in the larger picture of immigration.

If the civic-mindedness that created the murals is gone, the murals themselves have fared much better. In 1970, the Immigration and Naturalization Service sent a request to judge Jacob Mishler, Chief Judge of the Eastern Court of New York, to discard the works. But Mishler was struck by the murals, which reminded him of his father’s journey to America. He had them restored in a New York studio and in 1971 moved to the ceremonial courtroom in the federal courthouse in Brooklyn. He would ask the immigrants who passed through there “to look at it and remind themselves of what it means to become an American.” Since then, they have hung in the room where immigrants are naturalized.

The room erupted into applause as Judge Go’s speech ended. On her way out, though she had never met anyone there before, several people thanked her and shook her hand. Though for Go and the various clerks working in the courthouse this is a rote procedure, they expressed enthusiasm for the freshly minted citizens.

In a city that is 37 percent foreign-born, the Eastern District of New York courthouse in Brooklyn is the main site of naturalization. This ceremony was one of the four that take place every week in the courthouse, making it the site of over 50,000 new citizenships annually. According to US Citizenship and Immigration Services, about 680,000 new citizens are naturalized every year around the country, meaning close to 7 percent of all new American citizens pass through this room in Brooklyn.

As people exited the courtroom their families and friends, who were watching a live broadcast in the waiting room downstairs, lined up to greet them. They exchanged hugs and opened the packet of papers each citizen is given, which included a certificate of immigration. They made their way out of the courthouse, and collected their cameras and cellphones from the security guards downstairs.

Almost every one of the 267 paused outside the courtroom for one last rite: taking photographs as they held up their certificates. Some stood with their families; those alone asked others to take a quick snapshot. It was a finale, of sorts, to the long process of imagining themselves Americans.

Aesthetics mirror their times. Our imagination is central to the politics of immigration, but it will no longer look like Laning’s murals. The Ellis Island cycle offers us an ennobled, if toil-filled, American dream, linking a century of immigrant labor to the vast projects of the New Deal that funded the mural, and serving as a tribute to both.

The new Americans outside the courthouse in Brooklyn were emerging from a system that often makes opaque or immaterial the idea of citizenship, many of them rushing off to jobs in the new service economy. The murals in their solemn courtroom offered a history, but their photographs were a tangible claim, a celebration of their new stake in the country.