Milton Beame’s memories stretch 86 years and 1088 miles, but I first found them in a three-by-two-inch rectangle. It was printed beneath an ad for a cleaning service in the New York Post, which I was idly leafing through at a bar, looking for the horoscopes.

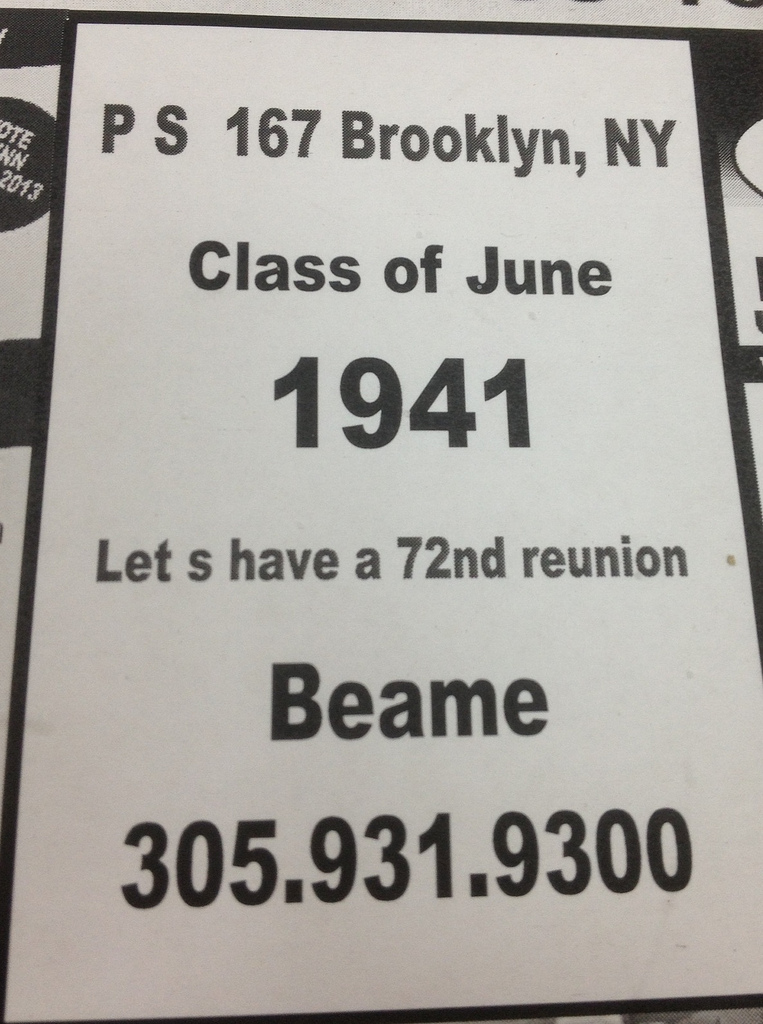

It read, “PS167 Brooklyn NY. Class of June, 1941. Let’s have a 72nd reunion. Beame.” A phone number was listed; area code: Miami.

Something about the grammar captivated me. It was so nonchalant. “Let’s have a reunion.” Let’s. Like “let’s take a stroll” or “let’s grab a cup of coffee.” I snapped a picture of it with my phone, and started on the crossword.

I didn’t call for a couple of weeks, but I never stopped thinking about Beame. I knew that when I finally sat down to call him, I would become part of his reunion. Milton didn’t sound surprised to hear from me. He answered on the second ring.

“Hello, is this Beame?” I asked.

“Yes, this is Milton Beame.”

“I’m a journalist living in New York, and I saw your ad,” I said.

A pause. “Which one?” Milton asked.

Turns out Milton had been spending hundreds of dollars to place his ad in papers in New York as well as Miami, where he now lives. The ad placed in the Post ran for seven days and cost $297. For $200, he got five placemat ads in Jewish diners (his graduating class was almost all Jewish) in popular Florida retirement spots.

P.S. 167 The Parkway is an elementary school in Crown Heights on Eastern Parkway between Troy and Schenectady avenues. When Milton attended, the school offered grades one through eight. He graduated 72 years ago.

“Is there any particular reason why you want to hold this reunion?” I asked.

Another pause. “Nostalgia.”

That’s the only explanation I could get from him over the phone. He told me that only two women had responded to his ad, one from the class of 1947 and one from 1946. He had the original program from his graduation and was going to start looking up names one by one. He asked if I would like to meet him and his wife Fran. They were taking a trip to New York the next week and were planning to visit the school.

I agreed immediately, and when I went home that night, I found a scanned copy of Milton’s graduation pamphlet in my email, along with a message:

Dear Shayla,

Until your call, I had given up. Perhaps your energy can revive the reunion.

Thanks and good luck,

Milton Beame

The four-page-long graduation program looked very formal for an eighth-grade ceremony. There were scriptures read and patriotic salutes to the flag. “Ballad for Americans,” a cantata popular during World War II, was sung before the address to the graduates. Awards for excellence were given in various categories — I saw that Milton had won the mathematics medal. Then a list of 60 boys and 60 girls. As I read over their names, I wondered who was still alive. Where did they live now? Most of the women would have changed their last names — how were we to find them? It was a list of fourteen-year-olds who had already lived out most of their lives.

But Milton wanted a reunion. Let’s have a 72nd reunion.

The next week, I waited for a call from Milton. On Wednesday, I got a voicemail as I came up from the Bleecker Street station downtown. Milton wanted me to meet him at 2:30 at P.S. 167. It was noon. I turned and went back into the subway — I wanted to get to the school first. Milton might have been able to walk onto the campus as he pleased in 1941, but I worried about showing up without notice.

I got off the 4 train at Utica Avenue and walked west along the parkway toward the school. A silent ice cream truck waited patiently for the school day to end.

Five stories high, with an orange brick facade and painted white parapets, P.S. 167 is an imposing structure. I walked through the oversized door and into the lobby, where a New York Police Department School Safety guard stopped me. After signing in with my driver’s license, I was sent straight to the office. There, a tired-looking secretary eyed me suspiciously as I explained that Milton was coming and that he was hoping to tour the school.

“I’m just not sure that’s going to be possible,” she said. “You have to call first. A lot has changed since he went here.”

She sent me outside to wait, and I sat on a bench in front of the school.

Milton and his wife, Fran, climbed up the stairs of the subway station. I recognized him immediately. On a crowded street in Crown Heights in 2013, an old Jewish man gleefully pointing at a school sticks out.

After a short introduction, Milton and I sized each other up. He had alert, clear eyes, combed grey hair, and a black Members Only jacket over a collared shirt tucked into jeans that sat high on his waist. Fran wandered around the block, taking photos with a digital camera. Milton sat down next to me and I told him that we wouldn’t be allowed in until 3:30, when the school day was officially over.

He didn’t seem to mind. He looked around the block and said, “It all looks exactly the same.”

Crown Heights, as Milton knew it, was a middle-class neighborhood. Many of its residents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who settled in the stately brownstones and townhouses near Eastern Parkway and in the apartment buildings beyond.

In those days, the benches that line the parkway, now bolted to the ground, were untethered. Residents could move them closer to a friend or into the sun or shade. In her book Crown Heights and Weeksville, neighborhood historian Wilhelmena Rhodes Kelly describes how the community gathered on stoops and benches, enjoying the fresh air and light of the verdant boulevard. It was a bustling, thriving neighborhood.

Abraham Beame, a mayor of New York in the seventies (and, coincidentally, Milton’s uncle), raised his family here. This is where John Oliver Killens, the celebrated black author of novels like And Then We Heard the Thunder, hosted gatherings of the Harlem Writers Guild at his apartment near Eastern Parkway. Clive Davis, the Grammy-winning record producer, grew up on Union Street.

In his autobiography, The Soundtrack of My Life, Davis reminisces about early summer evenings on the parkway. “The men would crowd outside the candy store waiting for the early editions of the next day’s newspapers to arrive, and the women would chat with one another and watch the children play,” he writes. “Every night you’d solve neighborhood, local, personal, and world problems sitting on the stoop.”

It seemed appropriate that Milton and I were meeting on the parkway, in the same communal space that had anchored life in the Crown Heights of his youth. We had an hour to wait, and in that time Milton took me back to the Eastern Parkway of his youth. There, across the street, was the bench where he used to sit with his “gang” — the group of kids whose friendship made such an impression that Milton was back, seven decades later.

Milton can name who lived in each house along the parkway. His family lived on Lincoln Place, one block north of the school. The bakery down the block, where Milton worked as a counter boy, is still there. It’s not the Jewish bakery Shuster’s anymore. Now it’s called Tropical House Baking Co.

Some of the gang used to race from their bench to Prospect Park and back or try to keep up with the Kingston Avenue trolley on foot.

That house, over there on President Street, is where Arnold Goldstein lived. A master at ping-pong (he had a table in his basement), Arnold won a tournament at school, taking the final match 21–2, even after switching to play with his weak hand.

Years later, Milton met his first wife, Roselyn, on that bench when he needed a date for an outing to the Paramount Theatre in Times Square.

“My friends wanted me to go, but I had already dated all the girls,” Milton said with a little smile. That’s when he saw a pretty girl approaching their bench. “In those days, you couldn’t ask a girl out on a Wednesday night for Friday night. So she said no, and I said, ‘Can I at least walk you home?’ And in the four houses down to her house, I changed her mind.”

After Milton graduated from P.S. 167, he went to Boys High School on Marcy Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant. He graduated in 1945 and enrolled in the City College School of Business and Civic Administration (now Baruch College). After a semester of college, he tried to enlist in the United States Army Air Corps but was rejected because he was color-blind. He was later drafted into the army (the war had just ended), and he served 21 months stateside. The day he returned from his service, Milton met Roselyn on the bench on Eastern Parkway. He re-enrolled at City College, where he majored in accounting. At first he lived at home in Crown Heights, but when he and Roselyn married, he moved out and they settled in Flatbush. While still in school, he got a job as an accountant at Arnold Constable and Company, a Fifth Avenue department store. Then, in 1950, two weeks after his graduation from college, he and Roselyn moved to Florida.

Milton hasn’t lived in New York since that move. In Florida, he and Roselyn had two children, Larry and Annette. They settled down to make a life together, but it was cut short. Roselyn developed melanoma, which ultimately claimed her life. She was 35.

Shortly after Roselyn’s death, Milton returned to New York and to his old neighborhood, just for a visit. His uncle was running for mayor at the time. Milton saw the flyers and buttons with his uncle’s name on them, but he didn’t call him. This wasn’t a social trip; it was a trip of self-reflection.

He felt he needed to move on. “After my wife died, I was a sad sack,” Milton said. “But I had two kids and couldn’t show it, and it was very difficult. One day I looked in the mirror, and said, ‘You had your time. It’s time to live your life.’”

Milton didn’t think about marriage again until he met Fran. They were set up by one of Milton’s accounting clients. After meeting Milton twice, Fran broke a date she had planned for New Year’s Eve to go out with Milton. It was their third date. They were married two months later, February 26, 1966.

“She was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen,” Milton said. Fran, still radiant now, wore a sapphire-blue coat that made her pearly white hair even whiter. She also grew up in Brooklyn, in Sea Gate on Coney Island.

“When you go back, the memories come flooding in,” she said. They had visited the Coney Island boardwalk the day before to eat a Nathan’s hot dog. They were both taken aback by the cost: $3.95.

“I used to pay 25 cents,” Fran said.

“I would pay ten cents,” Milton boasted, and pinched her arm.

“But I love each stage of life,” Fran said. “When you get to be our age, nostalgia is very powerful.”

Milton and Fran have been married for 47 years. She also has two children, Candace and Steve, from her first marriage, but Milton said their families were raised as one.

Milton and Fran visit New York about once a year. Each time, they take the train out to the Brighton Beach stop and walk along the boardwalk to get a hot dog. The last time they were here, about a year ago, Milton asked Fran if she wanted to see Crown Heights and his bench, where he used to spend his evenings across from the school.

“It’s not only the building — it’s the neighborhood,” Milton explained. “It’s not that we are always ecstatic about what we return to; we may be disappointed in a lot of cases. But when you go into Crown Heights, it hasn’t changed. The same buildings are here and are a hundred years old. I’m 86, and it was an old building when I was growing up!”

The sound of a bell reverberated from the school behind us. Children escaped through the doors and ran to cars, buses, and neighboring streets. We nudged past them and into the lobby. We signed in, and Milton and Fran slowly made their way up the marble steps toward the office. Milton paused on the stairs.

“You see those floorboards?” Milton said. He ran a weathered hand along the baseboards. “The superintendent used to let me and my friend Lionel into the Boy Scout meetings. We were eleven, and you had to be twelve. So Lionel and I would clean the floorboards, and he paid us ten cents and let us into the meetings.”

The boards, once bare wood, are now painted black. The moldings and baseboards are painted too. Students rushed past us on their way down the stairs.

Milton looked warmly at the children running down the same halls he used to, past the baseboards he used to clean.

I asked Milton how he felt returning to a neighborhood that had changed so much. He said that the last time he had visited Crown Heights, he had sat on his bench and noticed he was the only white person on the parkway. He said it didn’t change his neighborhood or his fond sentiments towards it.

“You talk about being, or not being, prejudiced,” Milton said. “It’s about being nice people, and it’s a pleasure to see them.”

When the hallways cleared out and the school day was officially over, we were shown into the principal’s office. Principal Marc Mardy sat us at a table in her large office, where she had arranged old documents and photos to show us. She is a short woman, but she stands up straight, giving the sense that she’s taller than she is. Her kind, deep voice sounds like it could soothe as well as reprimand.

Milton ran his fingers over framed pictures from the classes of 1931 and 1951 that lay on the table, searching for familiar faces.

“You don’t have ’41?” He looked disappointed. He picked some pieces of dust off the glass and stared at the faces of the children.

But graver than the missing photo was the news of an impending rupture in the school’s history. We learned that in March, the Department of Education had passed a proposal to phase out P.S. 167 and replace it with a Success Academy charter school. It seems Milton returned just in time. The charter school will begin operating next year. By June 2016, P.S. 167 will no longer exist.

Mardy said she is rushing to preserve the history of the school. There’s a lot to preserve. In many ways, the story of the school is the story of the neighborhood itself. As is true of any neighborhood in Brooklyn, the Crown Heights of today sits on top of many layers of its own history. What we see is not the whole story but merely what’s on top.

Pieces of P.S. 167’s history can be found all around the school. There’s a mural in the lobby dedicated to an early principal (born in 1883); in the basement sits the building’s original coal burner, which had its own ventilation system, now defunct. The burner dates to 1911, the year the school opened. When Mardy looks at the vent in her office, she is reminded that complicated air duct channels run through all the walls of the school, connecting each classroom and hallway as they have for the past one hundred years, and connecting the school to its beginnings.

In the school’s early years, Crown Heights was home to many middle-class city workers, who commuted to work on the Interborough Rapid Transit lines. The brownstones that lined the parkway were for the upper class. The proximity of the Brooklyn Museum, established in 1897, and Prospect Park made Crown Heights a desirable place to put down roots.

By the 1920s, many of the students at P.S. 167 were the children of immigrants, like Milton, who enrolled in the school a decade later.

Milton’s graduating class was almost entirely white. But the composition of the school began to shift in the 1940s, as chronicled by Brian Purnell in his history of the Congress of Racial Equality in Brooklyn, Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings. The P.S. 167 of that era, Purnell writes, had a diverse student body and a varied academic program. There were workshops on the fourth floor to teach trade skills. There was even a school newspaper, the P.S. 167 Tribune, which students printed on a press.

During World War II, the school, like many others, participated in the massive effort on the home front to support the United States’ war effort. A number of artifacts remain from that era. On a later visit, I saw the school’s pledge for victory, adorned with the U.S. seal and red, white, and blue stars. The pledge states that “each week, we shall engage in at least one activity, the sole purpose of which shall be to achieve a quick, just, and lasting victory, and with victory, freedom for all peoples.” Undersigned are the delegates of the classes and the student council.

There’s also a letter from Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., dated May 27, 1943, thanking the school for donations in support of the war effort. Milton’s class was too young to serve in World War II, but when we looked at the class of 1931’s photo, Mardy said that almost all the boys in the picture fought in the war.

Last May, a fire broke out in the school and seriously damaged many of the building’s walls. After the fire, workers discovered that children’s homework assignments had been stuffed inside the walls as insulation. Mardy said that in the early years after World War II, the crisp, flammable papers had been all the school could afford. The scribbled math problems and doodles of students long gone had been keeping the building warm for more than half a century.

I examined one of the pages — the charred paper was dated April 6, 1951. In faded cursive, a student named Anna did her “Dictionary Exercises,” spelling out words like “arraignment” and “executive” syllable by syllable.

When Anna attended P.S. 167 in the 1950s, Jim Crow was the law of the land in the South and de facto segregation the rule elsewhere. But P.S. 167 was a place of relative racial pluralism — Purnell describes its "multiracial, academically competitive learning environment."

Mardy said she believes that because the neighborhood was filled with different ethnicities from the start, the school’s early integration was seamless. The class photo from 1931 shows the school's first black student. Mardy said he was the son of an interracial couple: his mother was from Montserrat, and his father was European.

“It wasn’t always easy, but it looks like it was always a united, working-class neighborhood,” Mardy said. “I think the reason people come back to it is, it was a time that the community was really together.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, the demographics of the neighborhood shifted rapidly. An influx of immigrants from the Caribbean settled in the neighborhood, many of whom remain there today. Between 1960 and 1970, the neighborhood changed from predominantly white to predominantly black.

These decades were not kind to Crown Heights. Like many neighborhoods in Brooklyn, it was ravaged by the decline of the city’s industry and the flight of the middle class.

There was the 1977 blackout, the spiraling crack epidemic in the 1980s. And then there were the 1991 riots, which tore the community asunder and attracted international attention.

Like the neighborhood around it, P.S. 167 fell on harder times. James Haywood Rolling Jr. grew up in Crown Heights in the 1970s. Now an associate professor at Syracuse University, Rolling recalls the school’s decline in his collection of essays Cinderella Story: “As Crown Heights was abandoned to become a ghetto, the school building on my corner succumbed to the mediocrity of urban educational practices in America despite its impressive façade.”

Since Mardy took her job four years ago, she said, she’s been struggling to improve the school’s current academic structure and its test scores. It’s a hard task, made harder by widespread student poverty.

Much of the school’s effort goes into making sure the students have enough to eat. She said that one boy earlier that day had refused to take his standardized test because he was too hungry. Another was getting into fights trying to steal food to bring home to younger brothers and sisters.

According to data from the New York State Education Department, during the 2010–2011 school year, at least 91 percent of students at P.S. 167 came from families receiving public assistance. Mardy said a quarter of her students are in temporary housing and have no proper place to call home. They stay in shelters or with relatives.

“You look all around the world trying to help people,” Mardy said. “But hunger is happening right here.”

Members of the community appealed the proposal to phase out P.S. 167 at the DOE meeting on February 14. According to the public minutes from the meeting, Mardy, the head of the Parent Teacher Association, and a representative of City Councilwoman Letitia James all said the DOE was giving up on the school too quickly. They cited the economic downturn and challenges like poverty and crime as reasons for poor test scores.

But the proposal passed. Under the proposal, students who meet the academic standards of the new charter school will be allowed to stay. A glance from Mardy, and I know that few will have the chance to do so.

The class of 2013 of P.S. 167 will be the last graduating class with the school intact. The building will still exist, but the school will remain only as a memory, a layer of history. The graduation was held this week at the Brooklyn Museum.

“We’re going to try to make a celebration out of it,” Mardy said.

Another bell rang, signaling the end of after-school activities. It was almost 5 p.m., and an eerie silence fell over the school.

Vicky Walker, science teacher for 25 years, knocked on the door.

“You all ready, or should I just go home?” she joked. She was here to give Milton, Fran, and me a guided tour. We walked through the deserted hallways as custodians emptied trash cans and swept the floors.

“I wonder how many guys have run down and slid on these floors since I’ve been here,” Milton said. After our somber meeting with the principal, his spirit was coming back.

“If you did that in my day, they called your mother, and you got a shot on the rump for being a bad guy,” he said. He looked into a classroom. “Why aren’t the desks in rows? We had them in rows.”

“It encourages cooperative learning,” Walker said. She said a lot of people were going to lose a place they felt at home when the school closed. I asked where she would go. She said she wasn’t sure. We went into a stairwell, and Milton looked out the window.

“That’s where we used to play punchball! You wouldn’t see a truck there in my day. And there’s my building. We lived on the third floor.”

“Oh, no, that building is new,” Walker said from behind him. “They must have torn yours down and put that one up.”

Milton was quiet, and we continued down the steps.

We left P.S. 167 through the auditorium, where rows of wooden theater chairs faced an antique stage. On our way out of the deserted school, Milton stopped for a drink of water.

“Is this the cold water fountain?” Milton asked, bending over the rusted metal. Walker shook her head.

“Sorry, that one doesn’t even work,” she said.

With the school’s days numbered, Milton is racing the clock. He wants to organize his reunion before the school closes.

He put me in touch with June Vincente (formerly June Black), one of the women who saw his ads in Miami. June, who was in the P.S. 167 class of 1947, also lives in Florida. She is still close friends with six people from the Crown Heights elementary school. We talked on the phone about the possibility of a reunion.

“It’s hard to know what really motivates people, except that when you get to be a certain age, your old relationships become like family,” she said. “So he’ll start digging a little deeper, and maybe he’ll find someone that he can relate to, almost like a relative.”

June said she has no desire to go back to Crown Heights but would love to go to a reunion. As we talked, she started to remember things — running for class president, a choir teacher who was mean to her.

“She tested everybody for singing and walked along and told me, ‘You keep quiet!’ That stayed with me my whole life,” June said, laughing. “I never even wanted to sing ‘Happy Birthday.’ I just remembered her. All these names are coming back to me.”

June wrote to Milton afterwards: “You have opened up a treasure trove of memories. They are good ones. Thank you.”

Robert Goeman is the only member of P.S. 167’s class of 1941 with whom Milton has remained close. Milton calls him Bobby; Robert calls him Milt. Robert lives in New Jersey, close enough to the school to go back if he wanted to.

Shortly after talking to June, I met Robert at a cafe in Greenwich Village. He arrived early, carrying a framed copy of the class of 1941 graduation photo in a brown paper bag. Like Milton, Robert has the spark of a younger man. He has a small mouth that opens up to a big smile and is eager to share his memories. I can see why he and Milton are friends.

Robert explained to me why a reunion of P.S. 167 would be significant for him, more so than a high school reunion. Most of the kids in the neighborhood ended up at different schools throughout Brooklyn. P.S. 167 was the last time Milton, Robert, and their gang were all together.

“We had our crew of four or five guys,” Robert said. “It was a coming-of-age thing. We used to sit outside in the warm weather. There was that typical corner drugstore, with a soda fountain, that everybody hung out at.”

Robert lived in a brownstone directly across from the school. He remembered a nice girl in his building with whom he used to sit on his stoop and talk about mystery novels. Their favorite was The Saint by Leslie Charteris. They would call to each other in the stairwell with the Saint’s signature secret whistle.

“I tried to remember her name just now, and I can’t,” Robert smiled, with a shake of his head.

He pointed out himself and Milton in the graduation photo. Their prepubescent, chubby grins beamed up at me from the sepia picture. When Milton heard I had seen their photo, he said, “Don’t laugh too hard.”

Robert is skeptical about a reunion.

“It might just be you, me, and Milt,” he said. But as he looked at the faces of the children in his class, I could see the photo had a pull on him. I asked why he didn’t go back more often and visit his stoop. He tore his eyes away.

“Whatever memories I have, I’m fine the way they are,” he said.

Today, Milton and Fran are back at their home in Miami. Together they have four children, eight grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. They travel a lot and usually take one or two vacations a year besides their visit to New York. If you ever meet this pearly-haired couple with a quirky sense of humor and a penchant for reliving old memories, they’ll hand you their business card to keep in touch. It reads, “Milt and Fran Beame. Living Life.”

When he got back to Miami, Milton hired a typist who is working to find and contact the rest of the members of his class. While she has had little luck with the women, she dug up addresses for 53 of the 60 men. But 24 of the men, she found, had died.

“When I started this reunion project, I must have been dreaming that most of my class was still around and enjoying life,” Milton said. “I am feeling depressed, but I will continue.”

While the typist continues to hunt for the women, Milton faces the tedious job of mailing or calling each surviving classmate on his list. If all goes well, a reunion could be planned for the end of this year, either in Florida or in New York.

A few weeks ago, Milton called me to chat about whether the New York City municipal archives could be useful. As he spoke, my mind wandered. What would it feel like to answer the phone and hear a voice you hadn’t heard for 72 years? The last time Milton's classmates heard his voice, it belonged to a boy. It would be thrilling and bewildering. It would bring back a flood of settled memories, good and bad. Milton’s voice, clear and enthusiastic, brought me back to our conversation.

“What do you think about that? Should we pursue those archives?” he asked.

That’s when I realized the reunion was already happening within the world of Milton Beame. He brought the class of 1941 to life again.