“We were of the city, but somehow not in it,” the literary critic Alfred Kazin wrote of his childhood in Brownsville in the twenties and thirties. “We were the end of the line. We were the children of immigrants who had camped at the city’s back door, in New York’s rawest, remotest, cheapest ghetto.”

Remoteness has long defined the land upon which Brownsville sits today. When the Dutch settled here in the second half of the seventeenth century, they turned the area into farmland, which it remained for the better part of two hundred years. Then, in 1858, William Suydam, a landowner and real estate developer of sorts, had an idea: he wanted to subdivide his 30-acre property into 262 individual lots, to be developed with multi-family houses. But Suydam defaulted on his mortgages and the land was put up for auction, eventually ceding to a speculator, Charles S. Brown, for $12,000. Brown consolidated his purchase with a second parcel of land nearby. He understood that few New Yorkers would want to live way out by the Canarsie flats, and he marketed the village he developed — “Brown’s Village” — to the working class.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the neighborhood absorbed large numbers of poor Jewish immigrants. Many came to Brownsville from the Lower East Side in search of factory jobs, which were migrating across the river as foremen sought to avoid the neighborhood’s powerful labor unions. (The strategy backfired: sweatshop conditions in Brownsville’s factories were a major catalyst in the neighborhood’s political radicalization). The neighborhood became known for left-wing politics, electing Socialist and American Labor party candidates to the state assembly in the twenties and thirties.

Pitkin Avenue was a significant commercial thoroughfare, supplying the neighborhood’s working-class residents with everything they could need: meat and vegetables, clothing, furniture, jewelry. The neighborhood was poor, but not a place of abject hopelessness, and it produced a number of influential cultural figures during these years, including Kazin; the historians Howard Zinn and Meyer Schapiro; composer Aaron Copland; animator Max Fleischer, who brought Betty Boop and Popeye to the silver screen; and comedian Danny Kaye.

In the thirties and forties, a major business moved to Brownsville — but it wasn’t the kind of business that improves a neighborhood’s lot. The Mafia established an enforcement arm, the Murder, Inc. syndicate, recruited in part from Brownsville, and ran some of its operations out of Midnight Rose’s candy store on Saratoga Avenue. As Kazin wrote, the pressure to succeed in school and escape Brownsville was matched only by the fear of falling into the “criminal class,” the underworld run by mobsters like Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel.

After World War II, it was in Brownsville — far from the city’s economic heart and perpetually forgotten — that Robert Moses, the powerful planner and “master builder,” saw the opportunity for a radical experiment in urban planning. As historian Wendell Pritchett writes in Brownsville Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews and the Changing Face of the Ghetto, an examination of race and public policy in Brooklyn, Brownsville had no public housing as late as 1945, when Moses, at the apex of his influence, targeted the neighborhood for massive housing developments to contain — and isolate — the city’s working-class African-Americans, who were being forced out of desirable housing in Manhattan by racist real estate practices.

“Many questioned the need for such large developments,” Pritchett writes, “and raised concerns about concentrating public housing in a few areas” — one of which was the Lower East Side, where Moses’ public housing proposals were met with similar consternation. But Moses was undeterred. “Here again,” he said of Brownsville, “we have a neighborhood which needs to be cleared and apparently can be rehabilitated in no other way.” Mayor Fiorello La Guardia apparently agreed, stating that the projects were located in “undesirable areas where there is not the slightest possibility of rehabilitation through public enterprise.” Ignoring the cries of housing advocates, Moses rammed through the 1300-unit Brownsville Houses and, soon thereafter, a 1600-unit extension, later renamed the Van Dyke Houses. The arrival of the housing projects — and the concomitant isolation and concentrated poverty — presaged a bleak fate for the neighborhood.

In the late sixties, during John Lindsay’s mayoralty, Brownsville was scarred by riots and a series of bitter teachers’ strikes. In September 1967, a fourteen-year-old African-American boy named Richard Ross was shot by a black NYPD detective based on the suspicion that he and three accomplices had mugged an elderly Jewish man. In The Ungovernable City, a look at Lindsay’s New York, historian Vincent Cannato describes how Sonny Carson, a black nationalist and chairman of the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, called one of Lindsay’s aides after the boy was shot. “Some white cop has shot a kid in Brownsville,” Carson said, “and if the kid dies, Brooklyn’s going to burn.” Ross did die, sparking three days of anti-police demonstrations fanned by the rumor. The demonstrations turned violent, with bottle throwing, Molotov cocktail attacks, and looting; 150 police officers were sent in to quell the unrest.

The following year, Brownsville was at the center of a series of contentious teachers’ strikes that festered for six months; Time called the strikes one of Mayor Lindsay’s “Ten Plagues.”

In the early seventies, as the city’s economy weakened, the neighborhood, already in decline, went into free fall, leaving once-bustling Pitkin Avenue a shell of its former self. Homes were abandoned, left to decay, and rusting automobile husks littered the streets like locusts. Drugs and gangs moved in. The journalist Jimmy Breslin wrote in 1968 that Brownsville reminded him of Berlin after World War II.

Brownsville has never fully recovered. As urban migration revitalized communities like Park Slope, Fort Greene, and Williamsburg toward the end of the 20th century, Brownsville remained stuck in the past, a victim of circumstance and urban neglect. It looks much the same today as it did 50 years ago.

Playwright Elaine del Valle, creator of the autobiographical one-woman show Brownsville Bred, lived in the Langston Hughes housing project from 1971 to 1989. She was robbed at gunpoint at eight; at twelve, she barely escaped a violent rape. Her father died of AIDS. “The neighborhood is its own character,” del Valle wrote to me in an email. “One that both maximizes and limits your exposure, like a candle burning at both ends. You can witness a stabbing while never knowing how to properly use a knife to cut a steak.”

In the past two decades, Brownsville has continued to struggle. Crime has fallen, as it has across the city, but the spectre of violence remains, and the community is still poor. Poverty and violence are the main subjects of news reports on the neighborhood (even the occasional think pieces are bleak, with titles like “Brownsville, the Hood That NYC Left Behind” and “Where Optimism Feels Out of Reach”) and Brownsville continues to be closely associated with a litany of gloomy statistics. Thirty-nine percent of the neighborhood’s residents live below the federal poverty line, nearly twice the rate of the city as a whole, with an average household income shy of $23,000. According to the city health department, the three-year average infant mortality rate from 2009 to 2011 was the highest in New York City, at 9.2 deaths per 1,000 births, compared to 5.2 per 1,000 for the rest of the city. The 73rd Precinct of the NYPD, which patrols the area, reported the highest murder rate in the city in 2011.

By these measures and more, Brownsville is one of the most dangerous, distressed, and isolated neighborhoods in New York City. But on the ground in Brownsville, a different, more nuanced picture is starting to emerge, lit by a cautious optimism. Here, a multitude of community activists, urban developers, and concerned citizens are working with each other and the city to revitalize the neighborhood, by encouraging local economic development and combating entrenched poverty. Success will require a concerted and sustained grassroots effort.

I visited Brownsville one Saturday in June to meet Daniel Murphy, the executive director of the Pitkin Avenue Business Improvement District, and one of the most energetic community activists in Brownsville. In a sky-blue shirt printed with the words “pitkin avenue brooklyn, ny” on the front, “the place for everyone” on the back, the lifetime Brooklynite is directing a team of volunteers who are setting up an array of colored chairs, information kiosks, kiddie pools, and games — all the trappings of a street fair.

Murphy has served as the executive director of the Pitkin Avenue BID since January 2011. The BID, which functions as a partnership between the city and the neighborhood’s businesses, uses a formula common to the city’s 67 BIDs, in which a special tax on local businesses underwrites the maintenance and revitalization of a commercial area. Since it was founded in 1996, the Pitkin Avenue BID has provided sanitation, security, and beautification services in the area around Pitkin Avenue, east of Howard Avenue and west of Mother Gaston Boulevard. In July, the BID, in partnership with the Groundswell Community Mural Project, was awarded a $100,000 Our Town grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to fund “Transform/Restore Brownsville,” a project for which professional artists will work with Brownsville youths, probationers among them, to create public murals within the BID’s boundaries; one of the first will be on the side of a building at Pitkin and Strauss Street.

The BID also hosts events — the street fair is the third in a series known as Pitkin Avenue Summer Plaza. These events serve several purposes. They’re fun, of course, and provide an opportunity for participating organizations to do community outreach about public health and safety. But they also have an intangible practical benefit: they increase the sense that Brownsville is safe. That it’s OK to come out of your apartment and have a good time in public. In a neighborhood as beset by violent crime as Brownsville, that matters. “Believe it or not,” Murphy tells me, “this is public safety.”

With his close-cropped, graying hair and pale skin, Murphy, 43, visibly stands out in the mostly teenaged, and black crowd on Pitkin. (Brooklyn Community District 16, which encompasses Brownsville and Ocean Hill, was 76.2 percent black/African-American of non-Hispanic origin, as of the 2010 U.S. Census, and 1 percent white.) But beyond his physical appearance, Murphy seems to fit right in. As the afternoon wears on, his energy appears to intensify, and I frequently lose track of him in the block party melee, only to see him counting off a gunnysack race, snagging wiffleball pop-ups, or conferring with his team of blue-shirted volunteers. Nearby, a trio of firefighters screws a fitting onto a hydrant, which shoots jets of water in parabolic arcs into the street, and an emcee shouts out businesses on the block (Jimmy Jazz, Payless ShoeSource), as well as the 73rd Precinct.

The Pitkin Avenue BID is one of the many groups working together to alter the outside narrative of Brownsville, as well as to improve its health, safety, and self-image. The block party provides a good cross section of the intermixed forces working on the ground in the neighborhood.

At one end of the block, budget health insurance company EmblemHealth has parked a purple-and-yellow mobile truck, with a sliding window — it looks like a food truck, although instead of tacos, they’re spreading the word about health programs, like Medicare and Medicaid, local practitioners, as well as its own insurance options. “We’re facilitators,” says Johnny Cobos, a market segment manager. “We bring access right into the neighborhood.”

A couple of officers from the Community Affairs Bureau of the NYPD are also on-site, enrolling kids in Operation Safe Child. They’re registering each child’s name, weight, height, and date of birth into a database, and issuing picture ID cards to parents for their children. “In case they go missing,” one officer explains.

Akilah Wooten and Kenyatta Johnson, two representatives from the Brownsville Multi-Service Family Health Center, are distributing literature about healthy living and community gardens at a table next to the very popular face-painting workshop. With them is an energetic 23-year-old from East New York named Taylor Gordon, who manages the Brownsville Community Farmers Market on Rockaway and Sutter. Gordon shakes my hand and instinctively touches his heart. “Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve always enjoyed working with my grandma doing agricultural work,” he says. “That’s when I told myself I wanted a career as a community gardener, helping others that need the help.” Gordon got his first job at fourteen working with East New York Farms, a pair of community-run markets that promote sustainable agriculture and local economic development. The job changed his life. “The skills I developed over the years I can pass down to other young people in the community and encourage them to stay positive and think big,” he says. “Words can’t explain how it feels to see youths and senior citizens be positive and interested in eating healthy.”

Later, Murphy introduces me to Shirley Jones-Basen, a woman who managed — while undergoing dialysis sessions twice a week — to start a Girl Scout troop at Marcus Garvey Village, a housing project in the neighborhood. Jones-Basen, a lifelong Brownsville resident, is one of those people you meet and immediately know has been through a lot. Last year, she saw a two-year-old hit in a crossfire at the intersection of Chester and Riverdale, and was struck by the fear that something like that could befall her own young granddaughter.

There’s also the fear of violence that’s not random. It’s not uncommon for kids in the neighborhood to get involved with gangs before they reach high school. In June, the New York Daily News reported that a woman in the neighborhood found a .38-caliber handgun in her eleven-year-old son’s bedroom. In October 2011, a young mother picking up her child from school was shot and killed in the crossfire exchanged by warring gangs.

“Parents need to take back their children,” Jones-Basen says. “There are lots of resources here.” After witnessing the shooting of the two-year-old, Jones-Basen sought out interested parents through the tenant association at Marcus Garvey Village and created the Girl Scout troop, called Inside Hope. The goal of the troop is to give the kids a peer community that doesn’t involve gangbangers or drugs. Currently, there are fifteen girls in the troop, and a handful of volunteer leaders. They’re the ones painting faces at the block party.

Rosanne Haggerty, the founder and president of a group called Community Solutions, a national nonprofit that seeks to alleviate homelessness in impoverished areas, says that Brownsville “is a community with an awful lot to work with,” despite whatever troubles persist. Haggerty, who is spearheading a key revitalization effort in Brownsville, gained renown in the nineties for her work in supportive housing with Common Ground Community, another social services organization she founded, which eventually earned her a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, better known as the “Genius Grant.” One of her major projects with Common Ground was overseeing the renovation of a derelict hotel, the Times Square, transforming the building into a 652-unit homeless shelter with onsite counseling and medical services, along with a library, art studio, and rooftop garden.

In 2005, Haggerty and her staff were looking for a new pathway to ending homelessness, to get past the “same reactive mode of building more and more housing,” as she puts it. They began combing through a wealth of data that correlates with homelessness — welfare system involvement, incarceration rates, chronic disease, infant mortality — and found that there were only a handful of neighborhoods in New York that account for a majority of the city’s social distress. These neighborhoods are scarred by multi-generation struggles with entrenched poverty and crime. Brownsville not only ranked last on many of these social indicators, but it also lacked a strong, centralized social welfare organization that could help its residents.

Haggerty approached the Robin Hood Foundation, an anti-poverty organization bankrolled by hedge fund money, about working in one of these neighborhoods. It turned out that the foundation was interested in social services work in Brownsville, too. “There’s a phenomenon of these neighborhoods that are neglected and depleted, and don’t have a well-connected infrastructure to help people in times of crisis,” Haggerty says. She told the foundation she would like to help set up that infrastructure in Brownsville.

Community Solutions hit the ground with a typical community organizing approach: helping residents with practical matters like accessing government benefits and avoiding evictions. But Haggerty and her staff quickly realized that Brownsville lacked many of the institutions that can help residents sustain a higher quality of life over the long term: systems for early childhood support, alternative to incarceration programs, even budgeting courses.

“We realized that a different kind of approach would be needed to change the trajectory here,” Haggerty says. “The neighborhood lacked basically all of the ingredients of a safe, healthy, and prosperous community. No one program could close the gap.” And so in early 2008, Community Solutions launched the Brownsville Partnership, a community-wide, consensus-building organization, with the lofty aim of bringing into existence a healthy, prosperous neighborhood through grassroots organizing and networking.

Alarming rates of public assistance, incarceration, and homelessness are all symptoms of entrenched poverty, not root problems themselves, Haggerty explains. “Anyone who has lived in New York through its recovery from near-bankruptcy and disinvestment — who saw neighborhoods like Times Square, Harlem, and Williamsburg in the 1980s — knows that New York neighborhoods can be turned around. Brownsville has been neglected. That’s a big part of the reason it continues to struggle. The Brownsville Partnership is working to bring the same kind of steady investment, improved public services, and sustained, well-coordinated local action that has made such a difference in other communities.”

But gentrification does not seem forthcoming in Brownsville. Although the 3 and L trains run through the neighborhood, the density of the neighborhood’s public housing makes it an unlikely target for real estate developers. Brownsville has the greatest concentration of public housing in the country, with eighteen New York City Housing Authority developments. A third of the neighborhood’s approximately 60,000 residents live in public housing. This isn’t Williamsburg, Bushwick, or Bedford-Stuyvesant; there are no warehouses for artists to reconstitute as lofts and studios, no beautiful brownstones for families and young adults to move into.

Yet Brownsville’s sense of enclosure also protects it from the massive demographic upheavals caused by rapid influxes of wealth. Paradoxically, the prevalence of public housing and its distance from gentrifying neighborhoods could be one of the Brownsville’s greatest assets. It’s a place so isolated from the typical progression of urban revitalization that it can serve as a template for a different model of renewal — one, ideally, that can occur without the attendant disruption and displacement of unchecked development.

Creating and implementing that model is the primary goal of the Brownsville Partnership. “It’s fundamentally about building the community’s capacity to solve problems,” Haggerty explains. Since 2008, the Partnership has recruited over 20 nonprofits and city agencies, including SCO Family of Services, with which it established six early childhood programs; interfaith community organization East Brooklyn Congregations; and the New York City Department of Transportation. It has also also helped prevent 500 evictions, saving the city somewhere in the range of $35 million in shelter costs.

“Finding, recruiting and engaging partners is like dating,” says Rasmia Kirmani-Frye, the director of the Brownsville Partnership. “Although we’re polyamorous.”

Kirmani-Frye likes to describe the organization as a “hub,” connecting networks of problem-solvers and community residents. “The dominant narrative here is, ‘This is where people are shot and killed; there are no jobs here; everybody’s poor,’” she says. “And that’s what residents read. But the counter-narrative is that community exists here. It doesn’t need to be created.” She explains that communities aren’t just good at defining the problems that plague them — they also know what the solutions are. Or could be. Often what’s missing are the links that can “convene those ideas with organizations and entities and other residents, who can move them further along,” she explains. “What we’ve found, overwhelmingly, is that organizations were either doing work here but on a very small scale, or they wanted to be here. But the neighborhood lacked an anchor.”

Kirmani-Frye, who lives in Fort Greene with her husband and son, is a warm and gregarious advocate for grassroots organizing. Before joining the Brownsville Partnership, she was a full-time community organizer in Brooklyn, and she later taught courses on community mobilization and race relations at the New School while working toward her doctorate. The extent to which Kirmani-Frye’s work in Brownsville is a labor of love is palpable in any conversation with her about the neighborhood. On multiple occasions, other community leaders I spoke with referred to her as a critical resource for the neighborhood, someone whose humanitarian energy, organizational know-how, and deep roots in the community are essential to the operation of the Brownsville Partnership.

When Kirmani-Frye joined the Partnership in 2009, a man named Greg Jackson was serving as executive director, primarily in a community outreach role. He acted in that capacity until May of last year, when he suffered a fatal heart attack during a meeting of the Department of Parks and Recreation. He was 60. Jackson — or “Jocko,” as most who knew him called him — had decades of community organizing and youth mentoring experience in the neighborhood, lending him the credibility to reach at-risk youth and families, which was essential in the early days of Community Solutions’ work in Brownsville.

Jocko had been well known in Brownsville for a long time. A star point guard at nearby Samuel J. Tilden High School, he was drafted by the hometown New York Knicks in 1974. He split one season in the NBA with the Knicks and the Phoenix Suns; for home games in New York, he would suit up in Brownsville and take the subway to Madison Square Garden. After his retirement, Jackson returned to Brownsville, where he quickly became a tireless advocate for the community. He worked for the parks department in the eighties and, in 1997, assumed managership of the Brownsville Recreation Center on Linden Boulevard. Jackson transformed the rec center into a safe haven for community residents of all ages, staging talent shows and artistic showcases, renovating the building, chairing a youth basketball team, and organizing old-timers’ barbecues and games of softball and basketball. His endeavors earned him the honorific “Mayor of Brownsville.” Kirmani-Frye calls him “the most deliberate agent of hope I’ve ever met,” the “champion” of the neighborhood. Jackson’s legacy of “hope in action” is what she sees as the Brownsville Partnership’s higher calling.

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, urban theorist Jane Jacobs laid out a plan for “salvaging projects” by reintegrating low-income public housing into the surrounding neighborhood, and the neighborhood into the framework of the city as a whole.

“One of the unsustainable ideas behind projects is the very notion that they are projects, abstracted out of the ordinary city and set apart,” Jacobs wrote. “To think of salvaging or improving projects, as projects, is to repeat this root mistake. The aim should be to get that project, that patch upon the city, rewoven back into the fabric — and in the process of doing so, strengthen the surrounding fabric, too.” Here, she might have been writing directly about Brownsville: “Cut up physically by projects and their border vacuums, handicapped socially and economically by the isolation of too small neighborhoods, a city district cannot be a district in truth, coherent enough and large enough to count.”

One of the principal redevelopment goals of the Brownsville Partnership is to figure out how to implement Jacobs’ idea. Alexander Gorlin, an architect working pro bono for the partnership, mocked up conceptual site plans for the neighborhood’s housing projects that would connect them to the surrounding grid via a system of “laneways” — basically, a series of open-air esplanades that would replace underutilized plazas and parking lots, and which could be used for commercial development and pedestrian spaces. “People would love a sit-down restaurant, an Applebee’s like there is in Bed-Stuy,” Haggerty says. “A place where you could have a birthday party in Brownsville.” The plan would also add up to 1,000 new housing units to four adjacent complexes using infill development and rooftop additions.

“No one’s saying, ‘This is a cool space for whatever,’ so that allows for clearer revitalization,” Kirmani-Frye tells me, on a weekday driving tour through the neighborhood. Brownsville’s lack of a “cool” factor to outside developers means that the urban renewal that does occur can serve the needs of the community that already exists in the neighborhood, rather than a community to come. A vacant building can be repurposed into, say, a one-stop center providing residents with job opportunities, statistical data, and information about social services — something the Partnership dreams of doing — rather than becoming luxury condos.

Kirmani-Frye points out project after project, brutalist, peanut-butter-colored compounds like Tilden Houses (eight sixteen-story towers) and Howard Houses (ten low-rise buildings). “That doesn’t mean there aren’t opportunities to mix and improve housing, but you can do revitalization without displacing anyone. This is a community that has existed for decades.”

I ask Kirmani-Frye if there’s any concern that this is a kind of petri-dish community organizing. For 80 years, Brownsville has served as a testing ground for competing urban development theories — first Moses’ projects; then the Nehemiah Plan, which brought nearly 3,000 subsidized single-family homes to the area in the 1980s; and now Jacobs’ ideas, brought in by the Brownsville Partnership. Residents of Brownsville would have good reason to be suspicious of outsiders who claim the mantle of “community redevelopment.”

Kirmani-Frye says the concern is never far from her mind. Providing effective social support in a neighborhood like Brownsville requires social workers to be “nimble and innovative,” she says. “It’s different from being experimental. As we learn from residents what works and what doesn’t, we need to be able to adapt.” To help ward off those concerns, the Brownsville Partnership hires from the community as much as possible, and convenes summits with neighborhood residents to discuss common problems and brainstorm solutions. These workshops, which take the form of directed brainstorm sessions regarding parks and open spaces, crime and safety, and more, help determine the Partnership’s agenda.

The idea for the workshops sprang from a two-day event called the HOPE Summit, held in February by the partnership in conjunction with the Municipal Art Society of New York, a citywide nonprofit that encourages intelligent urban design. Over 200 people attended. The partnership provided maps, data charts, and photographs for community residents to identify and brainstorm solutions for underutilized neighborhood resources, troubled spots, and opportunities for both short- and long-term development.

A particularly visible result of this bottom-up approach to redevelopment is the bike lanes that have been laid down on Pitkin and East New York avenues. The bike lanes began with 76-year-old Bettie Kollock-Wallace, then the vice president (and currently the chair) of Community Board 16 and a member of a cycling club. Kollock-Wallace bemoaned the lack of safe route from Brownsville to Eastern Parkway and Prospect Park at a council meeting for residents interested in the physical design of the neighborhood. In response to Kollock-Wallace's concerns, the partnership convened planning sessions among the council, the Department of Transportation, bicycling and public transit advocacy group Transportation Alternatives, and Community Board 16. Now, cyclists are able to ride safely to the park.

“You’ve got Park Slope folks all bitching about the bike lanes, and no one thinks maybe Brownsville wants bike lanes?” Kirmani-Frye says. “That’s one of those things that’s transformational, yet easy to overlook, unless you’re listening.”

One of the Brownsville Partnership’s most active partners in the neighborhood is the Brownsville Community Justice Center, a project of the Center for Court Innovation, a public-private partnership that serves as the research and development arm of New York state’s court system.

James Brodick, the Brownsville Justice Center’s director, explains that the goal of the project is to provide occupational and social services to people who have encountered the criminal justice system, or are at risk of doing so. The hope is to prevent both recidivism and first-time offenses. “The whole reason we exist is to improve technologies within the criminal justice system, close the gaps in services, and offer more specific training related to underlying issues that bring people in front of judges,” Brodick says.

Brodick came to Brownsville in 2010 from the Red Hook Community Justice Center, a similar venture, which he founded in 2000 with the help of Kings County District Attorney Charles Hynes. The Red Hook center became the first multi-jurisdictional community court in the United States. Operating out of a refurbished Catholic school, a single judge hears cases from three police precincts that would ordinarily progress through civil, family, and criminal courts. The judge has a broad array of sanctions and services he can impose or offer, including community restoration projects and long-term drug and mental health treatment programs. The center also has an on-site clinic and a staff that connects youth to social reinforcement programs, including peer-education groups, GED courses and arts programs.

More importantly, though, the Red Hook Community Justice Center represents the possibility of improved relations between communities and the governments trying to serve them. By offering an array of unconventional programs and paying particular attention to the circumstances of each individual who comes to the court, the Red Hook Justice Center smooths tensions between at-risk youth and the criminal justice apparatus. In the thirteen years since it opened, the Red Hook center has lowered the use of jail sentences at arraignment in misdemeanor cases by 50 percent, and increased threefold community approval ratings for police, prosecutors, and judges.

Brodick is hoping the Brownsville center can realize these kinds of changes in the neighborhood. “There are a lot of people in Brownsville trying to get their lives back on track, trying to be positive,” he tells me. “But when they go back into the neighborhood, reality is reality. They have to deal with the past. We try to play a unique role — we’re affiliated with and connected to the criminal justice system, but we also see ourselves as an agent of change.”

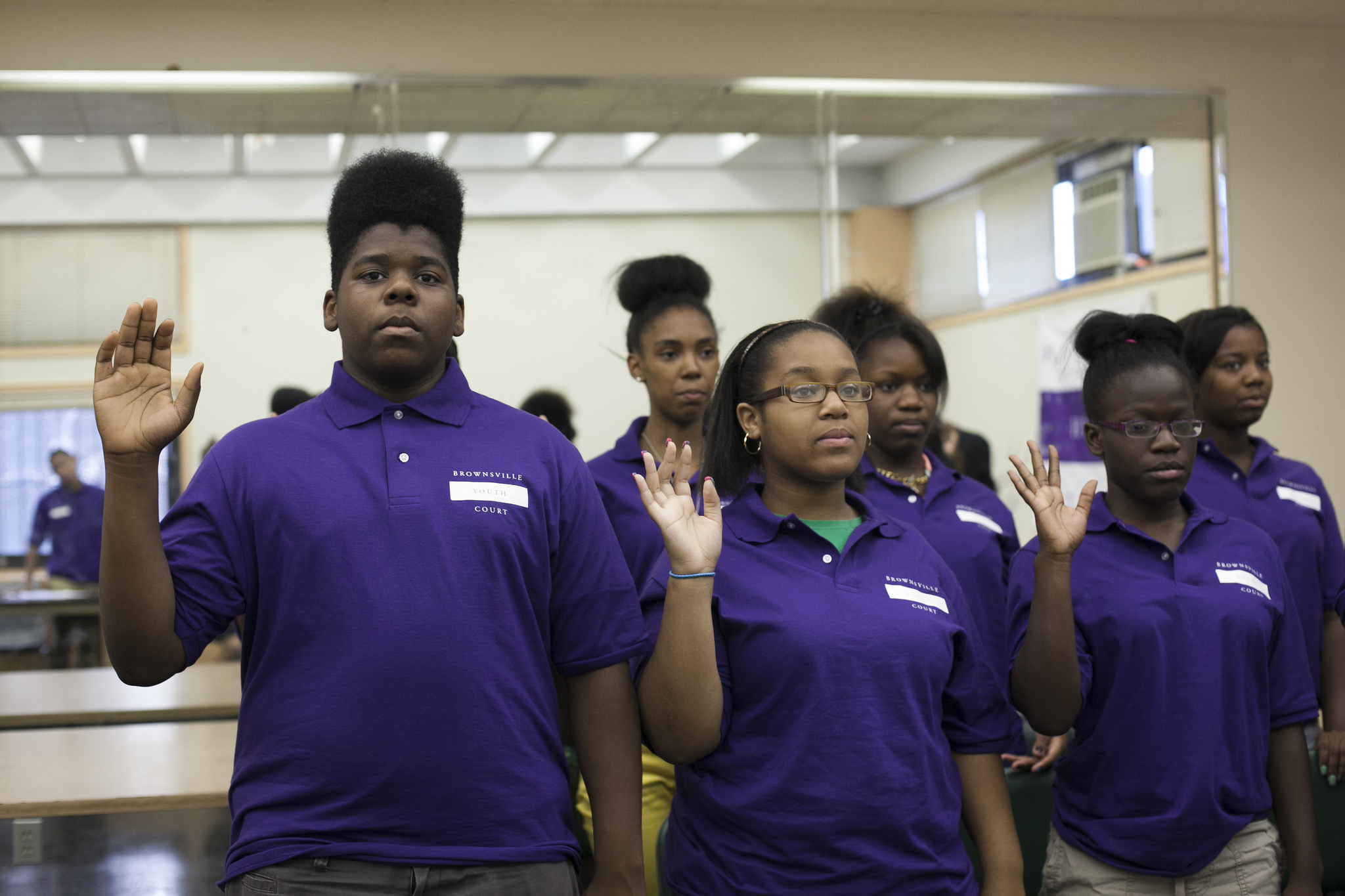

The Brownsville Justice Center currently operates out of an imposing, sterile building at 444 Thomas S. Boyland Street. The Brownsville Partnership is across the lobby. But although it is still young — Brodick estimates it will be about two years before it has a courtroom space of its own — the center has already begun offering programs similar to those in Red Hook. The cornerstone program is the Brownsville Youth Court, launched in May 2011, which trains teenagers to serve as judges, jurors and attorneys in cases involving peers who have been cited for small offenses (like vandalism, truancy, and low-level assault). Sentences include community service, decision-making workshops, and letters of apology. The goal is to exert positive peer pressure to ensure minor offenders pay back the community, while also keeping them out of the traditional court system. In late July, the court heard its 300th case. According to Sharese Crouther, a Youth Court coordinator, the compliance rate is 94 percent.

The Justice Center also runs the Brownsville Anti-Violence Project, which seeks to reduce violence and recidivism and improve police-community relations through programs such as monthly check-ins with recent parolees and public education campaigns that promote non-violence and cooperation with law enforcement. Last September, the program got a major boost in the form of a $599,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Justice. “It’s a little bit of a carrot-and-stick: we know who you are, we know what you’ve done in the past — if you continue to go down that road, collectively as a law enforcement group we will prosecute you,” explains Brodick. “But at the same time, we welcome you back home, we hope that you’ll be interested in programs and services, and we would like to work with you.”

The Anti-Violence Project is run by Erica Mateo, a young woman from the neighborhood, and Kayin Latson, who grew up in Crown Heights but often visited Brownsville to swim at the public Betsy Head Pool. Growing up, Mateo says, she rarely ventured beyond Brownsville’s boundaries; until she won a scholarship to attend Bard College, she’d only left the neighborhood once. While at Bard, she became an intern for the Brownsville Partnership, “until James poached me,” she jokes. She helped with another program before Brodick asked her to coordinate the Anti-Violence Project. “I’ve been through a lot of the growing pains myself,” she says. “I understand the violence, how people become so upset. I understand feeling desperate and hopeless and uninspired. I do this work because I don’t want other young people to feel that way.”

Latson’s family left New York for Los Angeles in the late eighties, where he got caught up with gangs. “I’ve seen how it affects the everyday psyche of a young man,” he says. After returning to New York, he met James Brodick at a meeting coordinated by District Attorney Hynes, and talked his way into a job with the upstart Brownsville center.

Everyone I spoke with at the Justice Center was hopeful about Brownsville’s future, but sober about the challenges the neighborhood faces. The first year of the program, Mateo says, the Justice Center had to figure out how to just get kids in the door. The ones they were getting were “really, really tough,” she says. Typical was one young gang-affiliated man on probation, who told Mateo he didn’t think he would live long enough to make committing to the Justice Center’s programs worthwhile. “How do I help someone set goals if they don’t think they’re going to live to see those come true?” she says, her voice rising. “We had to ask ourselves: what do we need to add to handle these cases?”

The center also has to navigate the often tense relationship between residents of Brownsville and the NYPD. Brownsville is a designated high-impact zone, meaning more cops on the corners. That can mean less crime on the corners, but it can also mean intense scrutiny and harassment for those who live in the neighborhood. There are lots of officers who get placed in Brownsville straight out of academy training without knowing much about the neighborhood, Latson explains. “They read the same things everyone else does,” which primes the officers to expect the worst. Brownsville consistently has the most stop-and-frisks, per-capita, of any neighborhood in the city. To help mitigate the tension, the Anti-Violence Project convenes monthly forums where parolees exiting the prison system can meet with law enforcement officials, social services providers, and former offenders who have gotten their lives back on track. The purpose of the meetings is to provide a support system for the parolees, as well as to humanize them in the eyes of the police.

Latson and Mateo have introduced themselves to many cops in the neighborhood to further this effort. “Folks in Brownsville just want to get home to their families at the end of the day,” Latson says. “You don’t have to high-five all the kinds when you see them, but you’re not on post in Afghanistan. You can be cordial.”

Brodick also introduced me to two young men from the neighborhood, Jerrell and Alonzo (because of the sensitive nature of our conversation, only their first names are used here), who both joined the center’s Justice Community program about two months ago. They were largely quiet during the discussion, as if they didn’t quite feel comfortable with their surroundings yet. But they were giving it a go.

Alonzo, a tall, lanky 20-year old, said he signed up for the Justice Community program “not only to build a better community, but to grow as a person.” He’d attended a community anti-violence meeting at his mother’s building, and met Darren Johnston, a case manager at the Justice Center. Now he’s participating in PhotoVoice, a program run in partnership with the Brooklyn Arts Council where young people photograph and interview Brownsville residents in an effort to portray the neighborhood in a more positive light.

Jerrell, who is 23 and was wearing a flat-brimmed Yankees cap and square-framed glasses, also joined the Justice Community program as a way to extricate himself from potential trouble. A former drug dealer, he says he wants the community to be better for his young son. Recently, with the help of the Justice Center, he obtained a job that he says will keep him off the corners.

Brodick pointed out that both men are exemplars of the untapped potential that has so often withered in Brownsville’s populace; both are at-risk young men who might have found themselves trapped in the same cycles of poverty and hopelessness that have marked the neighborhood for decades. And, of course, they still might — the draw of old habits and old ways is powerful.

“Before I got a job a couple of weeks ago, I wanted to sell drugs again,” Jerrell says. “I’d walk to the store, four people ask me for a bag of weed. Crackheads, dopeheads. It’s easy to do that here. But I’ve been to jail twice — 8 months, 4 months — and I’m not trying to go back. I’m trying not to be weak-minded anymore. I fight temptation every day. Every day. I always think about doing the right thing. The right thing is gonna make me live longer. Every day I look in the mirror and ask myself, ‘Is it worth it?’”

The unofficial motto of Brownsville is “never ran, never will.” It’s said pridefully, but considered another way, it also speaks to the neighborhood’s sense of perpetual isolation — from the heart of New York City, from affluence, from a broader sense of possibility. The isolation of Brownsville isn’t just physical — it’s psychological, too.When the symptoms of entrenched poverty have cycled through several generations, horizons become diminished, the world becomes smaller. That isn’t going to change overnight. But, for the first time in a long time, there’s real cause for optimism in Brownsville. There are the community champions, like Kirmani-Frye and Haggerty and Mateo and Latson, and then there are people like Jerrell, who are doing their best to improve themselves and their neighborhood a day at a time, doing their best to do “the right thing.” There are people like Shirley Jones-Basen, the Girl Scout troop leader, who is “not too hopeful” about the future of the neighborhood, but is trying to do something to make it better anyway.

“Change is coming to Brownsville, just like everywhere else,” says Daniel Murphy. “Change is inevitable. It’s up to us.”